TDN is proud to partner with the Keeneland Library and the Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries in a very special collaboration: the Keeneland ‘Life’s Work’ Oral History Project, a series of filmed interviews by TDN columnist Chris McGrath with significant figures in the Thoroughbred industry. The current installment, with Gus Koch of Claiborne Farm, appears here.

by Chris McGrath (11-minute read)

(Listen to this story as a podcast by clicking the arrow above.)

Legends, to you and me. Immortals, paragons. But to Gus Koch, they were the flesh-and-blood companions of his daily toil: some were cherished friends; others, just a pain in the butt. He worked with Natalma in Canada, her son Northern Dancer in Maryland, his son Nijinsky II at Claiborne.

It was at Claiborne, for 31 years, that Koch ran perhaps the most potent breeding shed in Turf history, having been hired as manager soon after the young Seth Hancock had taken the reins.

“Secretariat, of course, was the hype name for non-horse people,” Koch says. “Then we had Danzig, Mr. Prospector, and Nijinsky. Sir Ivor, Damascus. The stallions we had in that barn were just unbelievable.”

Great horses, and great horsemen, have been the fabric of his career. Even when he first met his future wife, Koch was giving a shot to a 31-year-old Triple Crown winner. A Sunday afternoon at Stoner Creek Stud, outside Paris, Kentucky; everyone else has gone home, and Count Fleet is down with colic. And here comes a car, a bunch of girls from Lexington, and one of them turns out to be Theresa. You never know what’s round the corner, whether with people or horses.

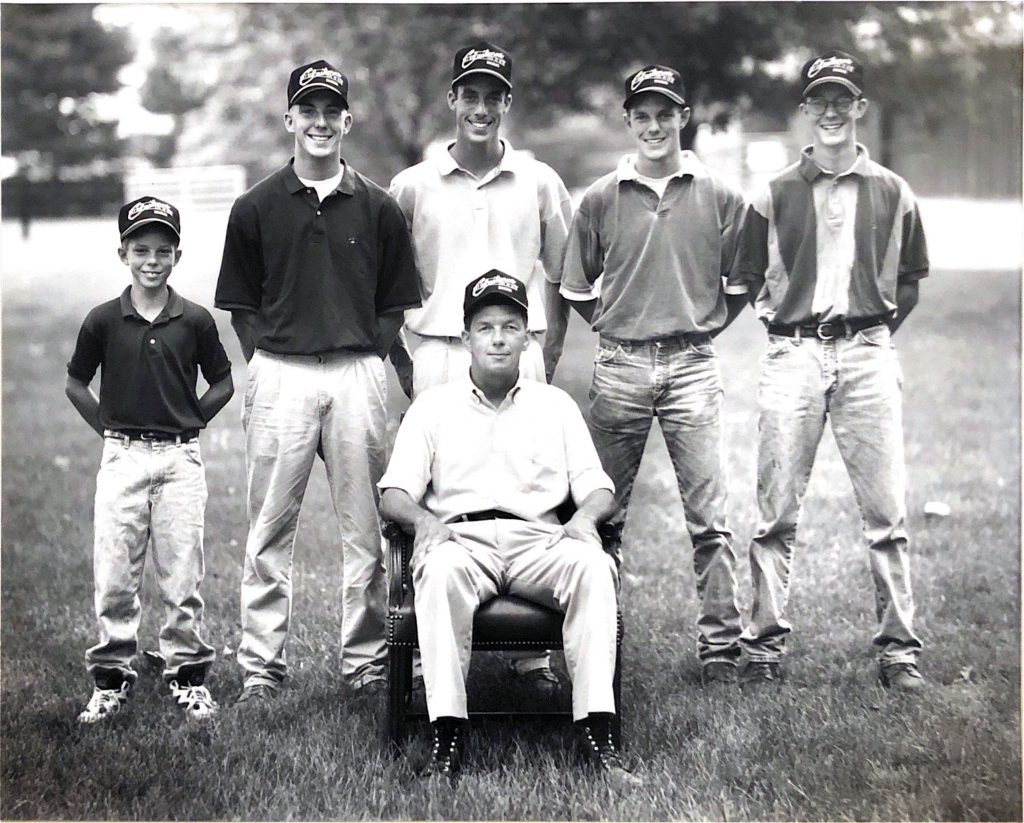

Now he sits at home at Mt. Carmel Farm, just a few miles up the road, his retirement sustained by pride in his ten children. All five boys have followed him into the horse business, and rather more directly than did Koch himself when–having grown up on a grain farm, north of Cincinnati–absorbing the interest of his father, who wrote for periodicals on agriculture as well as racing and sales.

As my legacy, to see my sons go on and do things I wasn’t able to do, it’s just awesome. They’re good horsemen, and they’re making a difference in the business.”

“We always had riding horses,” Koch recalls. “My first was a former lead pony from River Downs. Horse named Billy. I loved that horse. My dad just loved racing and we were always at the Keeneland sales, or at the old Latonia, or at a fair meet.”

Formative experiences, evidently. Nevertheless Koch likes to say that he lived in Ohio for 18 years but grew up in the United States Marine Corps. He had just left high school, Vietnam was beginning to smolder, and they had a Marine quota to fill the day he went before the draft board. Koch put his name down. That night he found himself in California, standing in line “on the yellow footprints,” waiting with suitcase in hand for the barber’s chair.

“And off all our hair comes,” he says. “There were some hippies in our group. I mean, I was a farm boy. But they had hair down to here. It was very hard on them. We had one guy in our draft who tried to kill himself, the second or third night. Even that was brutal. They called us out in the middle of the night. We’re in our skivvies. The drill instructor is going nuts. He’s got a bayonet. He said, ‘The next one of you idiots wants to try this, let me show you something. Don’t you cut across here. You put this bayonet in here. You take it all the way to your elbow and you better be dead when I find you.’ Oh yeah, he challenged us. It was very intense.”

But when he got to Vietnam, Koch understood the axiom: the more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war. And he is proud that his son Matthew also served in the Marines, as an intelligence officer, before maintaining respect for their surname in the Bluegrass community at Shawhan Place.

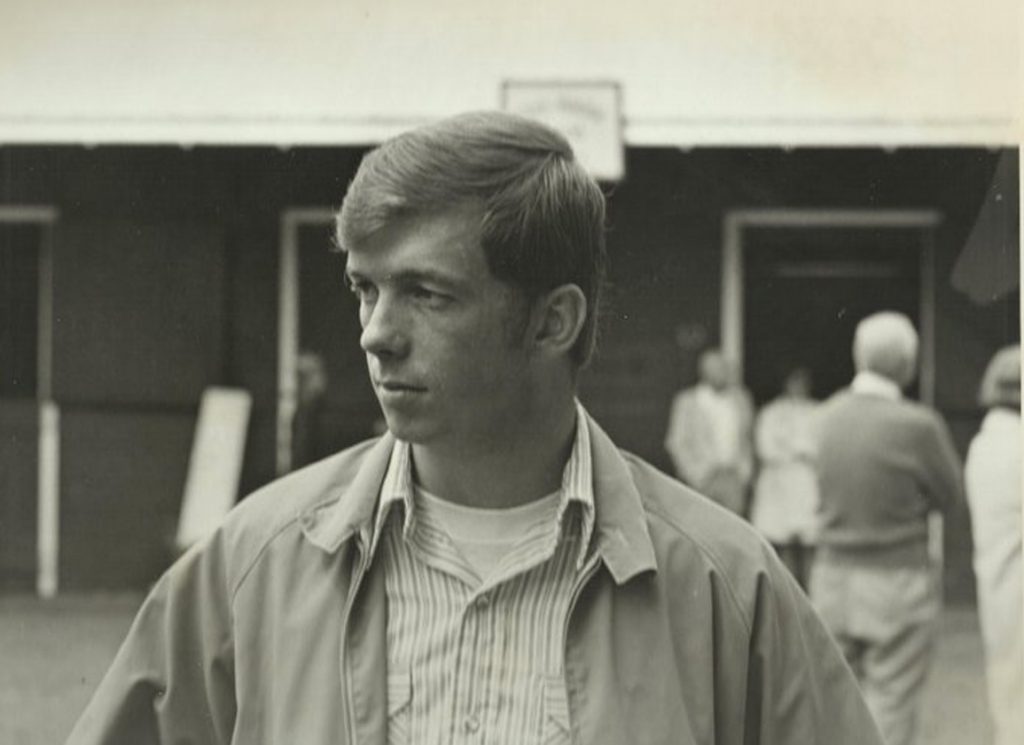

Koch’s own transition between the military and the bloodstock business began with an introduction to Charles Kenney at Stoner Creek, “the dean of Kentucky farm managers.”

When Koch entered his office, Kenney had a phone in each ear. “He told me: ‘Just wait a minute. I’ll take you home and have my bride fix us some lunch.’ Well, his bride was 75 years old. But anyhow, he offered me a job. Minimum wage was going up to $1.15 an hour.”

If Koch wanted more than that, he could go and work at Claiborne. They’d pay him better, but he’d be a nobody over there. As it was, by learning under Kenney, Koch would eventually arrive at the storied farm across the creek as a “somebody.”

I wasn’t the smartest one in the room, but by golly I could outwork any of them.”

He started on the feed truck, his allergies inflamed by the choking dust. Count Fleet was still around, as we already know–the old horse was terrified of storms–but he was about to retire from service and the farm’s new owners were into Standardbreds. Kenney took Koch to the Indiana State Fairgrounds to see the famous trotter Nevele Pride, prompted by three Thoroughbreds, set a world record at 1:54.8 for the mile.

“One of the best sporting events I’ve ever been to,” says Koch. “Very exciting. Then afterwards we go back to the barn, because now he’s coming to us [at Stoner Creek]. The groom from Sweden who had nine fingers was holding him. There wasn’t anybody within 35 feet of him. He was a vicious horse. Got me one day. He pulled me up, he had my blue jeans in his teeth, shaking them.”

Exposure to Standardbreds, including use of artificial insemination, gave Koch an intimate grasp of equine reproduction; and he was able to benefit from an outstanding mentor of the old school in Kenney.

“Mr. Kenny was a very educated man,” Koch emphasises. “He taught German at the University of Kentucky. He was like a second father to me. He worked me hard. He wanted the best for me. In fact, when it was time for me to go and move up, he was going to let me replace him.”

But Koch had his heart set on Thoroughbreds; and while five years with Standardbreds might seem a long way round, it was an invaluable grounding.

“Because it was so hands-on,” he explains. “We didn’t have a resident vet. We did so much of the animal care ourselves. We did all our own foaling. We had a problem, we had to take care of it. I looked at a lot of semen over the years. I know a little bit about semen! Not from the scientific standpoint, but ‘oh, yeah, here’s a viable sample.’ I’d take semen home with me, shock my mother-in-law. Sit it on the counter and see how long it would live. Get up at night and see if it was still alive.”

True, there was one occasion–at Claiborne, years later–when this amateur know-how missed its mark. Veterinarians weren’t permitted to analyse semen, with fertility insurance at issue, so a slide would instead be presented to Koch whenever a new stallion was test-bred. In 1995, the champion miler Lure arrived at the farm.

“Seth [Hancock] was standing right next to me,” Koch says wryly. “I looked at my microscope and said, ‘No problem here, boss.’ Those were my exact words. He was sterile. But none of the vets could figure it out either. His semen was fine. He just couldn’t stop mares for some reason.”

Marines don’t cry, but this one did when he left Stoner Creek. He had, however, received an offer he couldn’t refuse–from E.P. Taylor, to work with his breeding stock at Oshawa. And when he left the Ontario farm, five years later, Koch would cry then too.

“It was my kind of farm,” he explains. “Gravel roads, not real fancy, but just good people. The best. Mr. Taylor was getting old, he wasn’t on the farm that much now. But we had one attraction: his Fell ponies. They came from England, I guess they used them in the coal mines. And he’d ride them. He would come out and might look at Victoria Park or Viceregal, but he always looked at the Fell ponies, which we thought sort of a nuisance. He loved those ponies.”

At Oshawa Koch learned a new perspective on the raising of racehorses, closer to the English manner. And, in Natalma, he was dealing with one of the most important mares in the history of the breed.

One Christmas, Koch was sent to Maryland to bring Natalma back to Canada to foal. She had been covered by Nearctic, so was expecting a full-sibling to Northern Dancer.

“It was sleeting, snowing, nasty,” he says. “We loaded these mares up. They were worth a fortune. The drivers had had a few drinks, they’re passing each other [on the road] and all this silly stuff. I said, ‘That’s it. We’re not going any farther with these mares.’ Of course the driver wants to fight. I said, ‘I don’t care what you do with your truck. These horses aren’t going any place.’ We pulled over, he starts drinking some coffee and sobering up.”

There were other problems, down at the Maryland branch, that ultimately required Koch to uproot again. Resolving those problems was not enjoyable, but at least there was the opportunity to work with Northern Dancer and also with an Epsom Derby winner he had raised as a foal, a “tough little son of a gun” named The Minstrel.

“Everybody of course bred these great big mares to Northern Dancer, because he was so small,” says Koch. “We had a little pit where we could mount him easily. He was a very good breeding horse. Tough. Didn’t like people. He was not vicious but you had to watch him.”

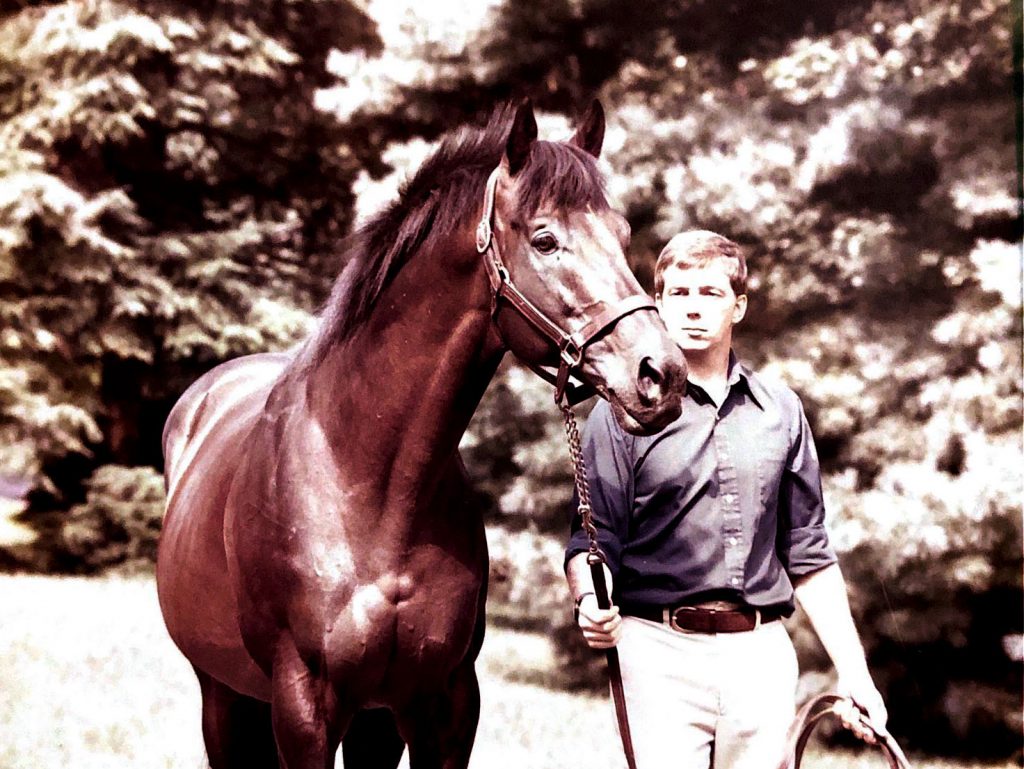

After completing his education with the little colossus who was transforming the international breed, Koch was ready to take over a stallion barn that would, in aggregate, achieve no less impact. Hancock approached him in 1977 on the recommendation of Stuart Janney, who had mares in Maryland as well as at Claiborne. Koch and his new boss were of similar age, and each sensed that the other was offering just what he was seeking.

“Seth needed somebody who could handle stallions, run a breeding shed, handle broodmares,” Koch recalls. “Do the whole thing. I just looked him in the eye and said, ‘Seth, I can do this. You want some references?’ He said, ‘No, I’m a pretty good judge of a man.’ I never asked him what he’d pay me. He never asked me what I wanted. We shook hands because both of us knew it was the right thing to do.”

Nijinsky II, himself a graduate of E.P. Taylor’s program, would become perhaps more cherished by Koch at Claiborne than any of his other illustrious charges.

“He was atypical for Northern Dancer: big, strong, lot of bone,” he says. “Good temperament. I loved the horse, spent so much time with him. Because he had a health condition, lymphangitis, in his right hind. Always the same time of year, when it got hot and humid, that leg would blow up.

“The vet [Dr. Walter Kaufman] and I worked straight through from the first foal in January, all the way until the July Sale. Then that Wednesday Doc would go to Hilton Head, and on the next Monday I would take my family to a local lake. Well, Nijinsky somehow knew when the vet left, and his leg would blow up. And there I was, dealing with that, and of course Lloyd’s of London would get involved, and every year the leg would get more scar tissue, and more severe.”

So Koch would stand with the horse for hours, running a cold hose, one as patient as the other. The Queen of England shared his regard for this princely horse: Koch remembers her arriving, “a camera around her neck just like all the tourists,” and asking whether they would be seeing Nijinsky. Which set her apart, because naturally everyone else wanted to see Secretariat.

“I’d be leaving the farm on a Saturday night, and here comes a vanload of people from Michigan,” recalls Koch. “‘We’re closed.’ ‘Aw, we just drove all day. We just want to see the big red horse.’ And I’d walk up there and show them Secretariat. That horse could load a camera. He loved to have his picture taken. One of the most photographed horses in history, I’m sure. He just never did a thing wrong: easy to breed, easy to handle, easy to keep his weight on. Until he got sick. Boy, that was tough. But we had said from day one, we’re not going to let this horse suffer. I was there when Dr. [Tom] Swerczek [pathologist] took his heart out, and said, ‘You know, biggest I’ve seen.’ I guess that was his secret.”

His Claiborne tenure having lasted as long as it did, until ill health precipitated his retirement in 2009, Koch presided not only over loss but regeneration; over the evolution of whole dynasties. He was there when Round Table, with his curious habit of biting himself, was pensioned; he saw Nijinsky cover Round Table’s sister Monarchy, to produce State; while the mating of State’s daughter Narrate with Mr. Prospector in turn gave the farm Preach, the dam of Pulpit.

“The day our vet got sick, State got the colic,” recalls Koch. “By the time I got another vet there, we’d lost her. I said, ‘Dr. Kaufman’s not even to the hospital yet, and we just killed Claiborne’s best mare. We’re not off to a good start here.’ But then she became the [great-]granddam of Pulpit. You know, it just keeps going.”

So Koch became a fixed point, a fulcrum, as these wonderful families were spreading out. Sometimes, his centrality to Claiborne seemed quite literal. Just as the tragic Swale was raised right in front of his house, for instance, so Koch was at the line when he finally won the farm its first Kentucky Derby.

I was hands-on, I was down in the trenches. And I loved it… I was an employee. But I watched that farm like I was a Hancock.”

“They just had such good mares,” he reflects, when asked to explain the magic of Claiborne. “Yes, the land, absolutely. It’s been proven to raise good horses. They don’t crowd them. And Seth was right there–just like his father was right there, just like his grandfather was right there. As the saying goes: ‘The master’s eye fattens the calf.’ They were right there on site, watching what was going on. And not innovators. Very slow to change. Everybody else had ultrasound machines before we got one.”

In the meantime, Gus and Theresa were building a dynasty of their own. The kids all learned the ropes around Claiborne, starting out weeding and mowing until earning their chance to handle the horses, too. “As my legacy, to see my sons go on and do things I wasn’t able to do, it’s just awesome,” Koch says. “They’re good horsemen, and they’re making a difference in the business.”

And that’s because they were all raised to understand how everything starts with the sweat of your brow. When Koch returned from his time with the Marines, he felt he had acquired one asset that would redress any deficiency: “I wasn’t the smartest one in the room, but by golly I could outwork any of them.”

As such, he treated every place he worked as though it were his own. So when the farm had success, he felt as though he owned part of that success. Not the farm itself, but its branding: Stoner Creek, Windfields, above all Claiborne. He apologises if any of this sounds “hokey”. But it’s what he believes.

“I don’t mean that I set out to outwork everybody,” he explains. “It’s just I couldn’t stand not to know what was going on. So when I met Seth at the office at 6:00 every morning, I was able to tell him everything that had happened during the night. I was hands-on, I was down in the trenches. And I loved it. I would tell the night man, the vet, the foreman: ‘Call me.’ I always had the farm radio with me. I was an employee. But I watched that farm like I was a Hancock.”