TDN is proud to partner with the Keeneland Library and the Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries in a very special new collaboration: the Keeneland ‘Life’s Work’ Oral History Project, a series of filmed interviews by TDN columnist Chris McGrath with significant figures in the Thoroughbred industry. The third of these, with Ted Bassett of Keeneland, appears here.

by Chris McGrath (15-minute read)

(To listen to this story as a podcast, click the play button above.)

Anyone privileged to know this gentleman will very soon know where I’m going with this.

The Eclipse Awards, 1984. He has been invited to announce the winner of a Horse of the Year duel between Slew o’ Gold and the venerable gelding John Henry, who has just turned 10. He finds that the envelope is stuck fast, and spends a few awkward seconds trying to tear it open. As the tension rises, he finally produces the card. And he doesn’t even announce the horse’s name. He simply says: “Like old wine…” and everyone is on their feet, applauding the horse who just gets better every year.

Ron McAnally, the trainer of John Henry and a good friend, bounds up there and reproaches him: “For goodness sake, I nearly had a heart attack waiting for you to open that thing.”

But just as there was no need to name John Henry that day, 35 years ago, nor can anyone really need to be told which pillar of the American Turf, in meanwhile advancing to the age of 98, has himself only been fortified, and never eroded, by the passing of the years–both in the vigour of his character, and the esteem of an industry.

It barely seems a figure of speech, in fact, to describe James E. Bassett III as a pillar of the American Turf. His whole bearing remains so upright that it condenses not only the indelible stamp of his wartime service, with the U.S. Marines, but also the authority and integrity he seamlessly transferred to civilian life.

Anybody stupid enough to turn down a job that paid $100,000 and an option of 5,000 shares, and instead take a job at Keeneland for $30,000, is not smart enough to run Kentucky Fried Chicken.”

And that’s why the scope of his reflections falls far beyond the customary remit of this series. Yes, there were always horses lurking in the background. His mother’s grandfather was a Confederate general who bred trotters when he returned to Kentucky after the Civil War–with a daughter of the governor of Mississippi which, as Bassett says wryly, “did not impede his progress.” And Bassett’s own father, having lost a banking job after the Crash, found work helping to run Jock Whitney’s Bluegrass farms; ending up, in fact, on the original board of directors at Keeneland. But that was never any kind of clue to Bassett’s eventual destiny, which would summon him to the world of Thoroughbreds only by the most circuitous of paths.

“My career has been rather nomadic,” Bassett muses. “I’ve been very fortunate that people have tolerated me, but I was beneficiary of a strange series of coincidences and happenstances. I would be among the list of missing persons if the Kentucky State Police, Keeneland and the Breeders’ Cup hadn’t all had some innate problem.”

He had come within an ace of being missing once and for all, back in Okinawa. At daybreak he was heading a patrol as a rifle platoon leader in Baker Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Marines–a proud association.

“The only regiment in the 246 years of Marine Corps history that ever lost its colors,” Bassett says. “That was on Bataan: MacArthur surrendered the United States forces, and the 4th was there. Many of the survivors died on the Bataan Death March. Well, when they restored the 4th, it gave the whole thing a feeling. And here I was, just greener than a gourd.

“We suddenly were ambushed, moving up through a little bit of a valley, and I was fortunate… How in the world I was hit in my hand? My critics said afterwards: ‘Bassett, you must have been waving your hand up in the air at the Japanese.’ Hell, I don’t know what I was doing, but I got shot through the hand and I got mortar in my knee. I’ve often thought of it, I could have gotten that bullet right there and been gone. And it was just fortuitous circumstance.”

That life-saving, split-second twist of fate took its place in what Bassett recognises as a life-changing experience, overall, with the Marine Corps.

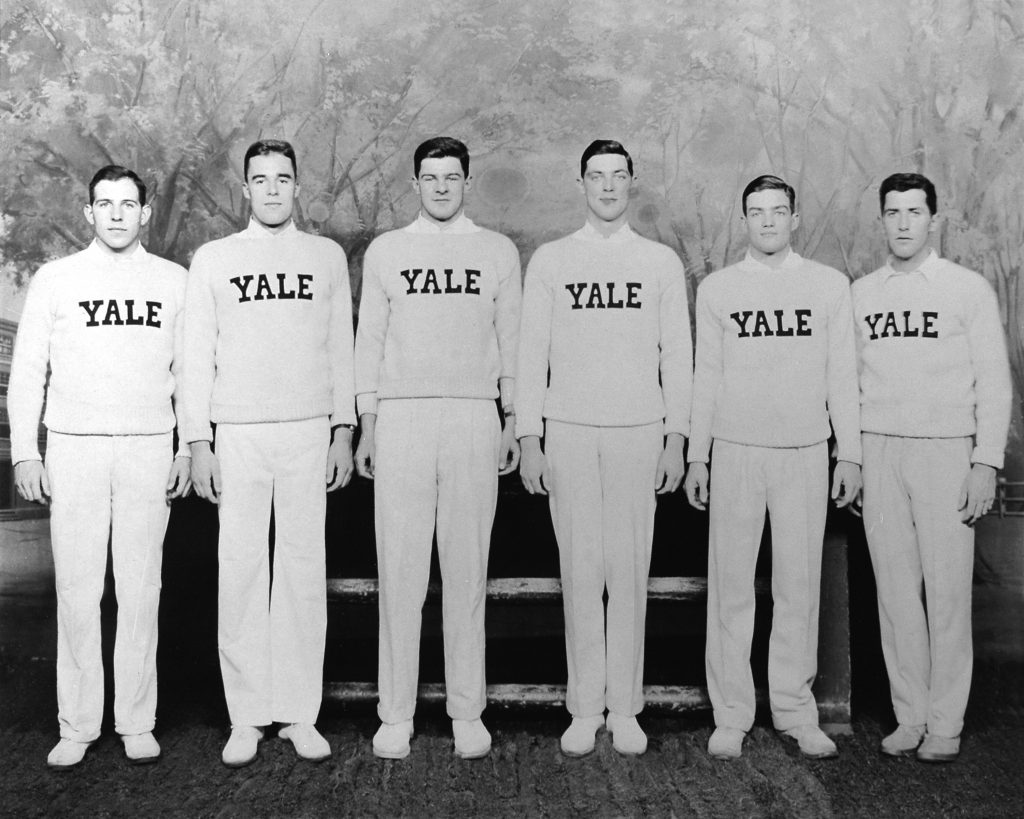

“It just never left,” he reflects. “It was that feeling. It was a swagger. It made a change in my life. A change in the commitment. I’m not waving a flag, but you had a feeling of ‘can do.’ Listen. If I’ve gone into the State Police as a Yale graduate, I don’t think I’d have gotten very far. But I went in there as a combat Marine, wounded and decorated.”

In the meantime, there had been the demob reward of young married life in post-war New York: South Pacific, My Fair Lady, $6 orchestra seats. He was a travelling salesman for a Whitney newsprint company, in the golden age of family-owned, community-oriented newspapers. But after an unusual interlude for a Yale graduate, as a tobacco farmer, Bassett and his wife Lucy were seeking a rather less literal way of going back to their Kentucky roots. And he found it, in the crucible of the Civil Rights era, in the State Police.

“It was the mid ’60s,” he recalls. “The nation was divided. School busing, open housing, equal pay. The riots: Watts, Alabama, Detroit, Rochester. Perception of law enforcement was at a very low ebb. You had Bull Connor in Birmingham, with police dogs attacking black mothers and small children. You had high-pressure water hoses and tear gas turned on these same people. You’d see the bodies rolling over, from the pressure of the hoses.”

When he took over the local force, Bassett found morale in the ranks at rock bottom. He pressed for better: both in the calibre of his officers, and in their rate of pay; worked to improve training, and public trust. One of the first things he did was negotiate some billboards pro bono. “And we had this good-looking, clean-cut state trooper, with his hat and whatnot,” he recalls. “And, in big red letters, ‘It’s my job to help you.’ And then we had the telephone number of the State Police post in that particular district. That was our first step, trying to say: ‘Friend not foe.'”

Bassett brought down the barriers. Troopers were sent into schools, groups of citizens were taken to the pistol range, or up in the helicopter. Borrowing the “long gray line” from West Point, he had the cars changed from blue-and-white to gray. There was a big spat when he brought in the blue light: the sheriffs wanted it, too, and Bassett said no, these were the very people–untrained, political appointees–from whom he needed to distinguish his own men. He set up what is now a major academic program at a local university, albeit he initially had to drag his men there with pay bonuses. To get speakers from the FBI he even went to see J. Edgar Hoover, and found him to be a horseplayer.

“That school over there now is a real factor,” Bassett says with due pride. “You know, in the old days, for firearm training you’d go with old Joe to the city dump and throw a Coke can up in the air.”

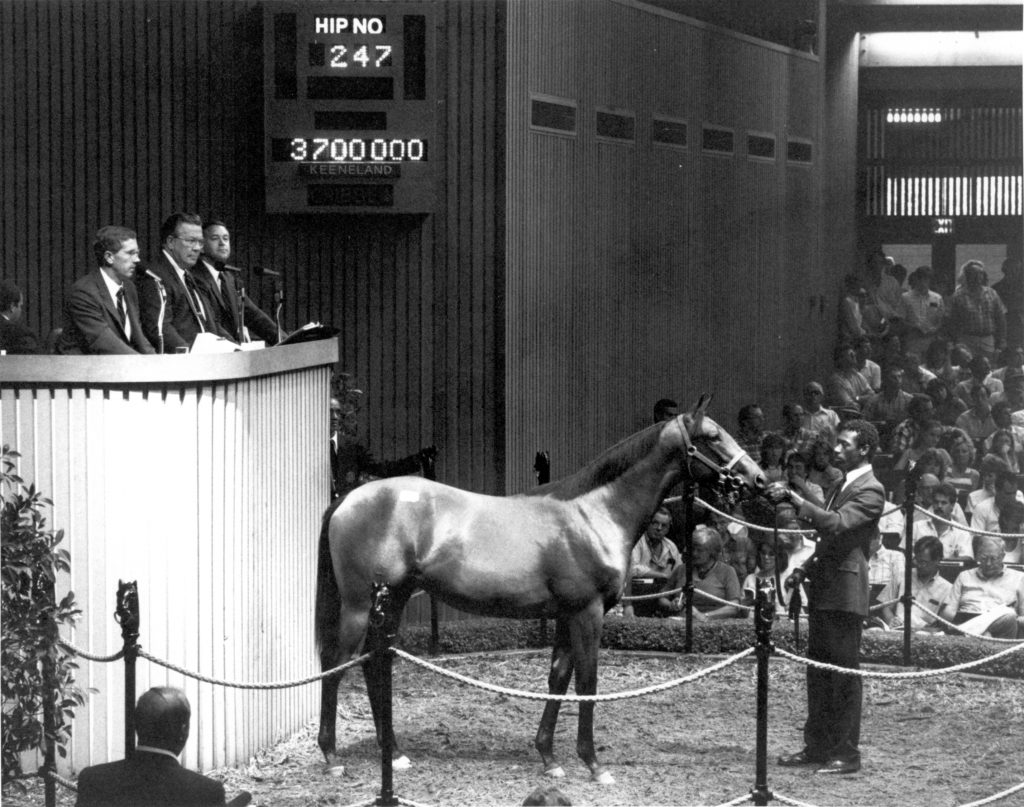

Looking back on those days, it was almost like an adventure movie. People from all around the world. Those bidding contests, the tension and silence in the entire pavilion.”

In establishing a reputation as a troubleshooter with the State Police, Bassett caught the attention of a very different institution; very different, but with one or two parallel issues in terms of a certain staleness, a need for structural and cultural adaptation to a rapidly changing environment: Keeneland.

“It wasn’t a personnel problem,” Bassett reflects. “But suddenly in the post-Depression years, Lexington began to grow. The interstates opened up Ohio and Tennessee. Keeneland was not prepared for this growth. And then there was Sir Ivor, opening up the international market for us.”

Bassett was so intrigued by the potential that he turned down three times the money from a somewhat less august local brand. Former Governor John Brown, who had purchased Kentucky Fried Chicken, still teases Bassett. “’You know, the luckiest thing that ever happened to KFC was that you didn’t take the job.’ I said, ‘Now John, wait a minute. What do you mean by that?’ He said, ‘Anybody stupid enough to turn down a job that paid $100,000 and an option of 5,000 shares, and instead take a job at Keeneland for $30,000, is not smart enough to run Kentucky Fried Chicken.’ And to this day he tells that goddamn story over and over again!”

As it was, he joined Keeneland at a time when the whole bloodstock market was on the brink of such seismic change that even its oldest hands were going to start afresh: to learn new rules, new ambitions, new names.

“We were like babes in the woods in many ways,” Bassett says. “We didn’t know the difference between a franc and a hot dog.”

French trainer Alec Head came in and tried to explain.

“They came in complaining,” Bassett recalls. “You know, our auctions, you have to be on your toes or you’re going to miss it. We were generally unaware of the language difficulties, and George Swinebroad was fundamentally a cattle and tobacco auctioneer [used to] selling maybe 15, 20, 30 cattle in a matter of 30 minutes. You have to listen, have to comprehend.”

But so, too, did Keeneland need to listen. Head’s bewilderment caused them to set up a bid display board, which would in time serve as the ultimate symbol of the market boom when the first ever $10 million bid, exceeding the seven digits available, caused the screen to go blank. That whole melodrama, with the Maktoum brothers duking it out with Coolmore, had come out of nowhere–or Dubai, which then amounted to much the same thing.

“Where was Dubai?” Bassett remembers asking. “I mean, we were that uninformed. They wanted to take over the 12th floor of the Hyatt on their first visit, and the hotel called and said, ‘Do you know these people?’ I said, ‘Well how do you spell their name? M-A-… Maktoum? No, never heard of them.’ But they were very low-key, making little or no demands, and had British representatives who helped pave the way.

“Looking back on those days, it was almost like an adventure movie. People from all around the world. Those bidding contests, the tension and silence in the entire pavilion. ‘I have 10.1. Anybody say 10.2?’ And everybody hanging on and Sangster bidding, Wayne Lukas bidding, it was like a boxing match. I was very fortunate to be a minuscule part, a bystander looking on. It was such a cast of characters coming in here.”

But that had been the case from the outset. He remembers an earlier record, at his very first July Sale: a $405,000 bid by an Italian American businessman from Virginia, trumping none other than Charles Englehard. The next day Bassett saw this unknown gentleman in the sales pavilion, introduced himself and thanked him for his support.

“And I said, ‘By the way Mr. Rosso, we do not have a financial report on you. Would you be kind enough to advise how you plan to pay?’ He was about five-six or -seven, and he looked at me in a quizzical, dramatic way, reached in his pocket, and took out four cashier’s checks for $100,000 and threw them at me. ‘Is that enough?’ And with that he turned and walked away. I felt about two inches high, but got down on my hands and knees and picked those checks up, took them in the office.”

From Signor Rosso to the Queen of England, Bassett has held his head high among them all. Actually, dropping a trophy in front of the Queen at Ascot one day contributed to his longevity, as what he presumed to be persistent bruising on his toe turned out to be a melanoma that he would otherwise have overlooked. On another occasion, he was asked to present the Melbourne Cup because Australia’s Labour Prime Minister had refused the dress code of top hat and tails. But Bassett conducts himself in exactly the same way with royalty or those who daily serve him breakfast in the Keeneland track kitchen: ever courteous, ever respectful of the true riches of human nature, which he knows have nothing to do with your bank balance.

For he has always adhered to the Marine principle of leadership, which is actually service. Put your men first, and they will see how to do the same for others. Though subsequently enlisted to bring the same team spirit to the Breeders’ Cup, Bassett remains ever the presiding spirit at Keeneland–which he views as a repository and symbol of beauty, tradition and service.

My career has been rather nomadic. I’ve been very fortunate that people have tolerated me, but I was beneficiary of a strange series of coincidences and happenstances.”

“Okay, it’s a challenge, over 85 years,” he says. “Emphasizing quality over quantity, aestheticism over commercialism, maintaining its unique position in the community–above all, its role of service to the industry, service to the community itself. Keeneland is more than just a racing and sales organization. We look on ourselves really as a responsible, caring citizen.

“I’m just fortunate. Fortunate as hell to have the opportunity to live in this community. To live in a place like Central Kentucky. It’s not only just the beauty of the place. It’s the beauty of the people. Caring people, kind people, thoughtful.”

The paradox of Bassett’s time here is that he had to preserve everything implied by the Keeneland name, its sober and reflective sense of heritage, through an era of giddy change–both on the track and in the sales ring.

“We try to set the standard,” he says. “Every time a new idea comes along, a newfangled idea of how to improve racing, how to get the fans out here, I always felt that the answer was: ‘flex, not cave.’ Look at it, try to see what’s good that you can adopt and use, but don’t cave in and throw out everything that you’ve done. This is the challenge as new administrations come on. They all like these new ideas. ‘Oh, they’re doing this in New York. They’re doing this in California.’ But the idea of beauty, tradition, location keeps intertwining. The purpose of what we had here was not to wring every last goddamn dollar out, but to do it in a pristine way that reflects the traditions of racing.”