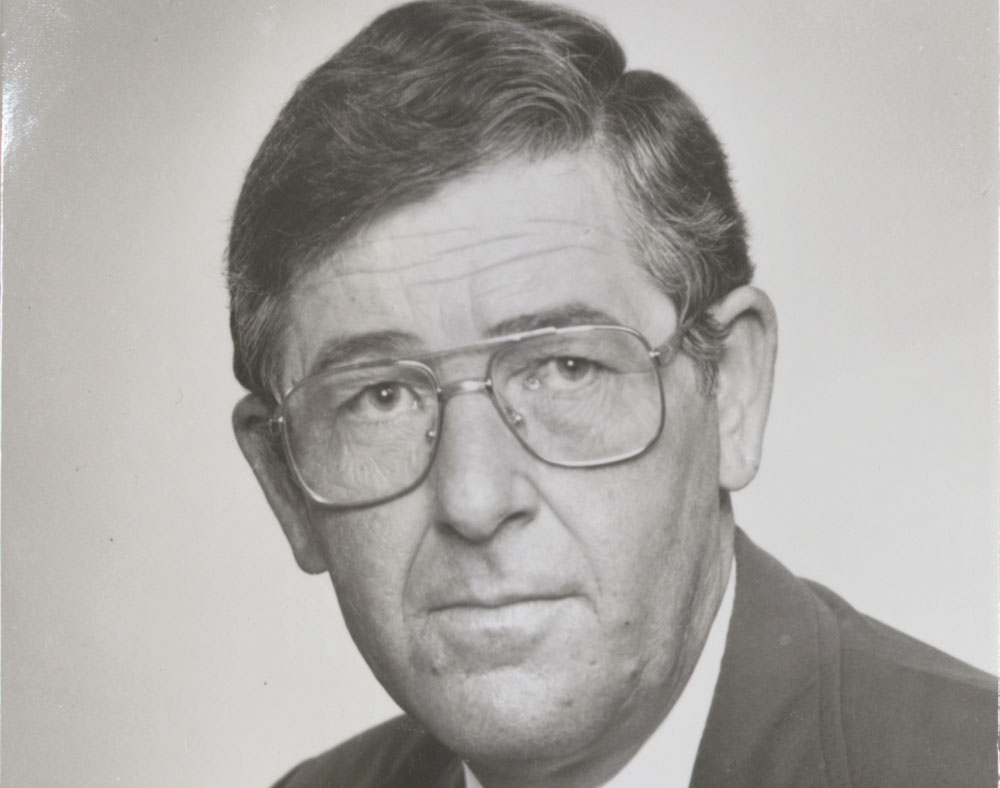

TDN is proud to partner with the Keeneland Library and the Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries in a very special collaboration: the Keeneland ‘Life’s Work’ Oral History Project, a series of filmed interviews by TDN columnist Chris McGrath with significant figures in the Thoroughbred industry. The current installment, with Dr. Gary Lavin, appears here.

by Chris McGrath (12-minute read)

(Listen to this story as a podcast by clicking above.)

As Will Rogers said, the best doctors in the world are the veterinarians–because their patients can’t talk. “And that’s true,” says Gary Lavin. “But at the same time, they don’t lie to you either. So that gives us an advantage right there.”

His long intimacy with the physical structure of the Thoroughbred has taught Lavin to marvel, above all, at those intangibles housed within. Instructively, in fact, this doyen of racetrack veterinarians has observed a correlation between their performance as athlete and as patient.

Ruffian, sadly, was an exception. Otherwise, however, Lavin has found that the better the horse, the easier he or she will be to manage. “Even under anaesthesia,” Lavin remarks. “Their pulse and respiration were all just textbook.”

“When I got to Churchill, surgery was in its very beginnings. That was the summer Tim Tam broke down in the Belmont and went to the University of Pennsylvania for his surgery. I’ve always marked that as the time, when it made the front page of the Daily Racing Form for weeks after, that people knew it was possible.”

In the 100th running of the Kentucky Derby, the roughhouse contested by 23 starters in 1974, the outsider Flip Sal broke down in the backstretch.

“When I got over there, he was in that spot where they take horses they’re going to euthanize,” Lavin recalls. “It was an ankle, same thing that had done Ruffian in. He wasn’t pawing or anything, he was just standing there. The hospital was just off the racetrack, and I suggested that we just take him over there, see how he would cool out and go from there.”

Lavin and his esteemed colleague Dr. Robert Copelan found the horse still composed and quiet the next morning. “He had a good pulse in his pastern and we decided, well, we’ll just see what happens,” he says. “We snugged him up in a tight bandage and, day by day by day, finally we put a cast on him. And he spent the entire summer there. And, of course, Dr. Copelan and I got all the credit for doing a wonderful job. All we did feed him, clean [his] stall and change the cast. That horse saved himself, is what happened.”

Maybe so; though perhaps Lavin’s characteristic modesty contributes to this assessment. This, after all, is a man whose work with the racehorse–from claimers to champions, for over three decades as racetrack vet–is measured by an alphabet soup spelling out his peers’ esteem: past president of the American Association of Equine Practitioners and Kentucky Thoroughbred Association; winner of the Bellwether Medal for Distinguished Leadership from the University of Pennsylvania; steward of The Jockey Club; trustee of T.O.B.A. and the Breeders’ Cup; director of Keeneland; vice-chairman of the Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation, etc.

So here’s a man who has long put the practical into the practitioner, trusted by elite horsemen to maintain that fragile margin where their dreams meet sinew, bone and ligament. He was born among them, after all, “a racetrack brat.” Though his family has Kentucky roots, and his grandfather was a doctor, the medical and Bluegrass strands only became entwined when Lavin–himself born in New Orleans; raised in Arkansas; and trained in Pennsylvania–cut his teeth, after qualifying in 1962, by sitting in with Dr. William R. McGee of Hagyard-Davidson-McGee.

The idea was to learn about broodmares. The racetrack, young Lavin knew about. His father, an assistant trainer for Greentree in California before the war, had then “dug bullets out of mules coming off the Burma trail” before working his way from gate crew to racing secretary at Keeneland; and then to similar appointments from Churchill to Oaklawn to Delaware.

“He was very good at the job and knew everybody,” Lavin says. “He was that kind of person, well liked and very successful. Having grown up in that atmosphere, I knew more than a little something–maybe not as much as I thought, but a whole lot–about the front side and how all that worked.”

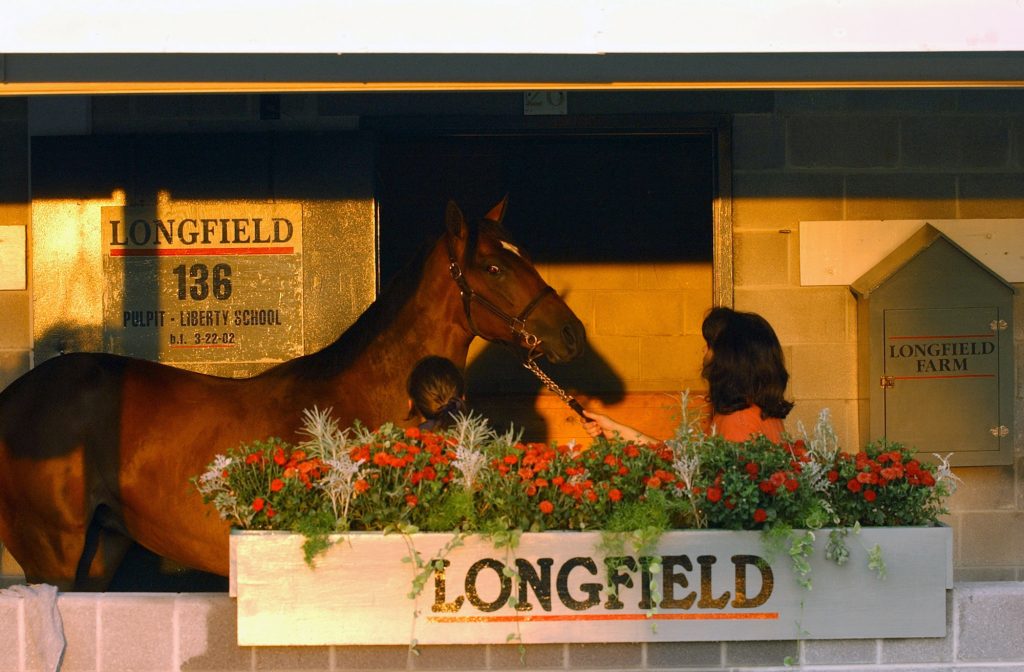

By now married to Betsy, Lavin bought a 40-acre plot adjacent to Hermitage; and was hired by his neighbour Warner L. Jones as farm vet. True, while their own Longfield Farm would expand in size and importance until ultimately producing consecutive Preakness winners, the position at Hermitage didn’t last very long. This was 1964, the early days of palpating. And for some reason the mares were struggling to conceive.

“And the farm manager, oh, Scipio Napier… never forget him,” Lavin recalls wryly. “Everybody called him Skippy, but there wasn’t much Skippy about him. He was a hard-nosed old hermit. Laid out the farm pretty much like an army base. He decided that it was the palpating that was the reason we weren’t getting mares in foal.”

Jones summoned Lavin and announced that the previous vet would be coming back to resume responsibility for the mares.

Well, that wasn’t going to leave Lavin a lot except the youngsters and indignity. “Deep down in me somewhere I got courage enough to say, ‘Mr. Jones, if that be the case, why don’t you just let Dr. Cochran have the rest of it and I’ll just go my way.’ But as it turned out, having lost him as a client, we became partners in almost everything you can do in the horse business before it was all over. He was one of a kind: a street fighter, but could just charm almost anybody.”

As so often in life, an apparent step back launched two steps forward. Growing up around the track, Lavin had admired the veterinarians who could work for any barn but were beholden to none. And it so happened that he returned to that environment at a time when science was transforming his professional possibilities–above all, thanks to more effective tranquilizers.

“When I got to Churchill, surgery was in its very beginnings,” he recalls. “That was the summer Tim Tam broke down in the Belmont and went to the University of Pennsylvania for his surgery. I’ve always marked that as the time, when it made the front page of the Daily Racing Form for weeks after, that people knew it was possible.”

Or take the flexible endoscope. When Lavin qualified, they were still using a rigid scope. “And along with the fact that you really couldn’t trust the tranquilizer, at that time, you had to have a very, very good reason–or had to be very, very brave–to insert that three-foot stick up through a horse’s head. It was a different, different world.”

Mind you, they would still dispense veterinary prescriptions at Wagner’s Pharmacy, ’round the corner. With limited literacy among the backstretch staff, the recipes would be numbered. “So Dr. Young’s No. 4 was for colic,” explains Lavin. “Sunny Jim Fitzsimmons’ No. 7 was a working [blister] paint. And so on.”

Some treatments, however, were rather more contentious. Especially, Lavin found, those introduced by out-of-town horsemen, almost invariably in a brown paper bag. Lavin would put them in the trunk, pull up somewhere and throw them into the trash. When Canonero II arrived from Venezuela in 1971, one of his crew who could speak a little English approached Lavin on Derby morning and asked what might he might legally use “to put a horse on his toes.”

It’s a performance-enhancing drug. It’s a debilitating drug. Dehydrates them. In the same breath, it’s the very same thing your grandmother in her wheelchair takes every morning. Now, you tell me that this is a dangerous drug. It’s innocuous. The worst thing about Lasix is that it is so innocuous.”

“In those days, the rules were very simple,” observes Lavin. “You didn’t use narcotics, of course. You couldn’t use depressants, or stimulants, or anything actually that would interfere with the testing. [But] that opened it up to all the steroids and things, which were fairly new at the time. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘On this particular day, Derby day, you don’t need anything like that. Canonero will be perfectly fine.'”

In the event, of course, Canonero was more than fine and exploded past 17 horses to win going away. But the story reflects Lavin’s vexation with a misplaced faith, among some horsemen, in medication as some kind of occult, transformative box of tricks.

“Lasix is the one everybody loves to talk about,” he says wearily. “I hate to talk about it, but I will. It’s a performance-enhancing drug. It’s a debilitating drug. Dehydrates them. In the same breath, it’s the very same thing your grandmother in her wheelchair takes every morning. Now, you tell me that this is a dangerous drug. It’s innocuous. The worst thing about Lasix is that it is so innocuous.

“You can make up any story you want, some people are going to believe it. There was a statistic the other day about the number of stakes winners last year that did not race on Lasix. Of the 408 stakes or something, I think there were 11 of them. Ridiculous. What a waste of money.

“Of course, I’m enough of an old fogey, we didn’t have Lasix when I started. We were into the ’90s before a horse won a Derby on Lasix. So what’s the big deal? But if that trainer across the street is winning more races than you, and he’s adding a little peanut butter and jelly to his evening meal… Do I have to tell you the rest of it? You’d sell a whole lot of peanut butter and jelly on the backside.”

For better or worse, times have changed. Think back to Flip Sal himself, and the assets he was able to offer when salvaged for a stud career. To whatever extent his redemption should be credited to his doctors, you won’t find many nowadays who have made 24 starts by the May of their 3-year-old careers.

Lavin likes to remind people that Seabiscuit ran 35 times as a 2-year-old. And some years, though he was working at the track at least 300 days, he didn’t have to destroy a single horse. On the other hand, the lower mileage of the modern era Lavin attributes not so much to the horse, as to trainers.

“If anything, we are growing a stronger horse,” he suggests. “Simply because they’re not worming [i.e. their systems are protected by modern treatments]. You keep the worms out of them, everything they’re eating goes into making them, not necessarily bigger, but I would bet that they’re a little bigger than when I started. Certainly they’re stronger.”

But fortitude, in horses no less than in people, is not just a matter of physical reserves. Having been at such pains to deprecate his role in the redemption of Flip Sal, it comes as no surprise to hear Lavin share a story that vividly sustains what we might call the Will Rogers principle.

“Doc, this horse, he’s just not quite feeling right. I think he’s a little uncomfortable. My wife and I are going out for the evening and I’d feel a lot better if you could just take a look at him.”

As far as Lavin recalls, the most he might have done was administer a small shot of tranquilizer. Essentially there didn’t seem to be a thing wrong with him. Next morning, the phone rang again.

“Doc, I got to tell you, we came home last night and this horse was dead.”

“Well, how about that?” says Lavin now. “I went by there on my way home, and the horse was dead–that was a good diagnosis. But in that stall there wasn’t one piece of straw out of place, nothing messed up at all. So we sent him up to the university for an autopsy. Sure enough, he had ruptured his stomach. Now this is one of the worst things you could wish on a horse. Yet he didn’t so much as dig a little place in the floor.”

And if a horse can be judged only by this inscrutable veneer, then horsemen must beware of pushing for answers. Much of the time, in fact, Lavin feels you can trust them to train themselves. He compares an experienced racehorse to the football player who doesn’t feel on song, when getting up in the morning, but who still runs out onto the field and just manages his game. As Lavin tells his son, who works in insurance, a horse with a bowed tendon tends to be a secure policy–because it will always train and race inside the limit.

As such, he is always wary of inflexible protocols. “Because if you keep looking, you’re going to find things,” he reasons. “Particularly in the older horse.”

One of his cherished clients, four-time Indianapolis 500 winner A. J. Foyt, once made a resonant remark about his own brand of horsepower. Asked by Lavin how his vehicle was going, he replied: “Well, at 210 [mph], it’s going okay. But at 211 now, at 211 there’s a little bit of a rumble.”

Another time, Foyt observed a surgery on one of his horses. As he was sewing up, Lavin remarked on the similarities between their work, in terms of keeping the conveyance going. “But there’s one big difference between my patient and your patient: we don’t have any spare parts.”

Any true horseman, as such, will feel an affinity with Lavin. Because he absolutely shares the same fixation with the racehorse; has always known that maximising its well-being will also maximise its potential. That’s not just a matter of his professional toolbag. It’s the full spectrum, from choosing the right matings to the state of the tack room. As Lavin likes to say, not least after working so long with D. Wayne Lukas, “there’s more to horse training than training horses.”

For over 30 years, he was in daily contact with racetrack paragons on two legs and four. He remembers an audience with Secretariat himself one morning at Churchill: Eddie Sweat walking the champ up and down, and then standing him up. The awed silence, finally broken only when his groom said: “Isn’t he the grandest-looking horse you ever saw?”

“And I said, ‘No.’ And he looked at me like… He didn’t turn loose of the horse, but he wished he could. And he said, ‘Well now, who is?’ And I didn’t blink an eye, I just said, ‘Majestic Prince.’ Well, that stopped him. The reason being Secretariat was such a different kind of horse from Majestic Prince. If you took those two side-by-side, and had a horseman pick the one they’d like to have, I’d love to know where it would finish. If they wanted a horse that’ll run three-quarters, seven-eighths, they’d all say Secretariat. But a two-turn horse, it’d be Majestic Prince. So there you are.”

No rules, then. Lavin, of course, reveres both horses as all-time greats: he’s purely remarking on the difference in phenotype, characterising Secretariat as the equivalent of a “tight end” and Majestic Prince as a “wide receiver.” No rules–and fewer short cuts. Forego had the worst-looking legs Lavin ever saw on a horse. And he reckons that if you conduct 200 cardiograms, at best “you might find a couple you wouldn’t want.” But he also knows that if you get things right, you do improve the odds. He knows that, because he himself raised back-to-back Preakness winners: Pine Bluff and Prairie Bayou.

For the little parcel of land by Hermitage Farm expanded, at one point, to as many as 700 acres; and, between boarders and their own Longfield Farm band, to a hundred mares.

Prairie Bayou certainly showed there are no rules: his pedigree was so mediocre that they had him castrated while he was being broken in Ocala. Another of Lavin’s patients, Sea Hero, beat him with the cleaner trip in the Derby but missed the board at Pimlico; as such, Prairie Bayou only had to finish the Belmont to get a seven-figure bonus for bossing the series. Tragically, however, finish he didn’t.

The silver lining to his loss was that Paul Mellon, Sea Hero’s owner, presented the bonus to the Grayson Foundation–an institution Lavin is proud to count among the many he has served, pro bono.

Pine Bluff’s story also had a gratifying sequel. Her dam delivered a full-sister who was, however, badly crooked in front. She was trained only with a view to establishing her potential merit, as a guide to the level of covering she warranted. Sure enough, she cruised home in her maiden but broke down when trying for a stake on her second start. At the Loblolly dispersal, Lavin confided to Arthur Hancock that she was the most talented animal the stable ever had. Hancock paid $525,000 and bred her to Mr. Prospector.

We go back that day and tell Geoffrey [Russell] we’ve seen the sale-topper. We not only made him the sale-topper, we made him the Derby winner. Walt Disney wouldn’t be silly enough to make a film like that.”

In 1998, Lavin went to Stone Farm as part of the Keeneland inspection team. A couple of years previously he had quit the track practice, tired out by 33 years on the backside. It was a refreshing change, and this was to prove its most rewarding morning: a first meeting with Fusaichi Pegasus.

“You know what they look like, late March in Kentucky,” he says. “And Arthur’s always raised them like Mother Nature intended. So we went out to look at him. He and I talk about it still. Never had a brush on him, and he’s ready to have his picture made. We go back that day and tell Geoffrey [Russell] we’ve seen the sale-topper. We not only made him the sale-topper, we made him the Derby winner. Walt Disney wouldn’t be silly enough to make a film like that.”

If they did make a movie, of course, you could hardly confine the script to the horses. You’d find yourself back in the silent era. As it is, the breed is fortunate that its mute needs should be legible to a man like this; and the whole Kentucky horse community, likewise, that he should have been cast in such a valuable role.