TDN is proud to partner with the Keeneland Library and the Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries in a very special new collaboration: the Keeneland ‘Life’s Work’ Oral History Project, a series of filmed interviews by TDN columnist Chris McGrath with significant figures in the Thoroughbred industry. The fourth of these, with Rick Nichols of Shadwell Farm, appears here.

by Chris McGrath (11-minute read)

(To listen to this story as a podcast, click the icon above.)

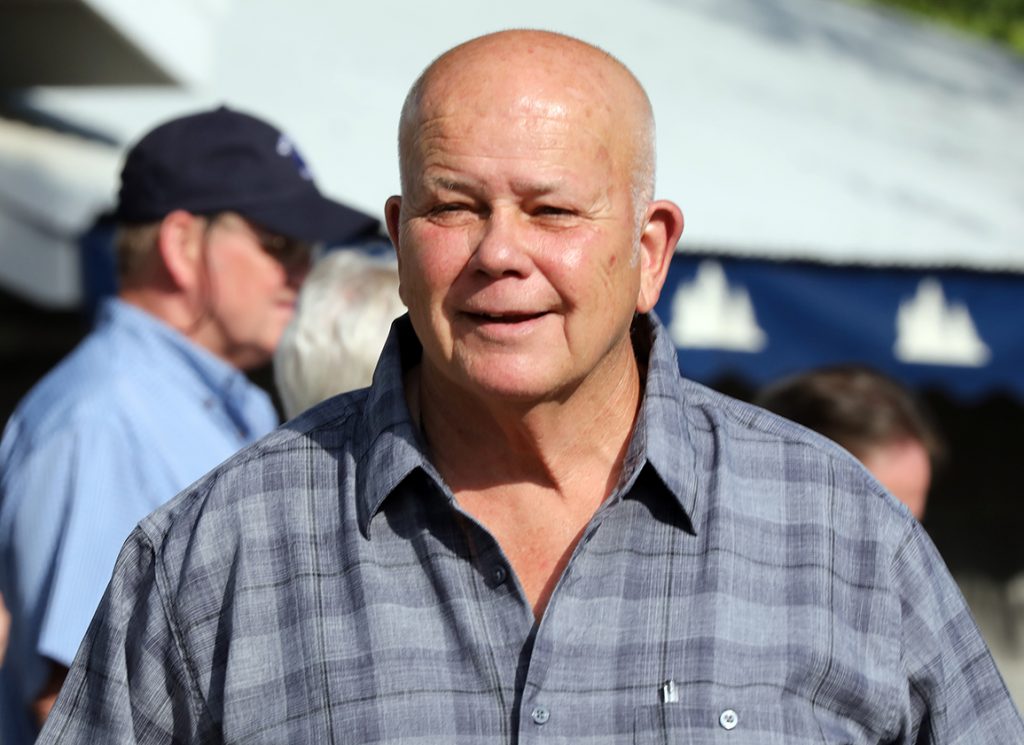

In hindsight, the trust and fidelity that have united Rick Nichols and his patron over the past 35 years were transparently available within the first 35 seconds they had anything to do with each other.

Sheikh Hamdan was then making his first bold incursions into the international bloodstock market; Nichols was in charge of the broodmare division at Spendthrift.

The Sheikh had come back for a second look at Mashteen, a young mare entered for the 1981 Keeneland November Sale. She was a graded stakes winner by Majestic Prince, but it was precisely such ruthless culling that had made Spendthrift’s broodmare band what it was.

“If they had two bad foals, they were gone,” Nichols recalls. “That was the case with Mashteen. Sheikh Hamdan came to look at her. The first time, he didn’t say anything. When he came back I said, ‘Sir, this mare has had two bad foals. It might be good if you looked elsewhere.’ He just looked at me and said, ‘Well thank you.'”

The Sheikh gave $1 million for the mare.

“That was when Nelson Bunker Hunt was trying to corner the silver market,” says Nichols. “At the price of silver, she was worth her weight in silver that day.”

When Nichols was hired to supervise Shadwell’s new Kentucky division, soon afterwards, Mashteen delivered a filly by Blushing Groom (Fr). “And she was crooked,” he recalls. “When he came to see her, the Sheikh looked at her and said, ‘I guess I should have heeded your advice.'”

But to leave the story there would not be Nichols’s style. To leave the story there, in fact, would dilute the candour that has rendered him so indispensable to his employer ever since.

“She went on and produced a filly that won him I think a Grade II and two Grade IIIs,” he says. “So yeah, we were both right.”

Nichols’s recruitment had been handled by Shadwell’s European managers, and it was only after he had come aboard that he was asked to Royal Ascot to be reintroduced to his new boss.

“I go over there, get all dressed up,” he says. “Back then they had a little house by the walking ring. I go and sit down and talk to him for a while. Sheikh Maktoum comes in, sits down, we talk a little bit. Then all the other Arabs, and English managers and trainers, and everybody started flowing in. And I just kind of sat back, trying to take in this new world I just got thrown into.”

At the end of the afternoon Sheikh Maktoum said to his brother, in their own language, “Your American is very quiet.” And that autumn he asked his own manager to reserve a specific name for his best weanling.

“A couple of years later we were at Newmarket, and a [bay] colt goes up the track in Sheikh Maktoum’s colours,” Nichols recalls. “The boss is looking at him through his binoculars. He said, ‘Do you know what that horse’s name is? Quiet American. He’s named after you.'”

So Nichols is guaranteed a lasting imprint on the Stud Book, through the sire of Real Quiet and grandsire of Midnight Lute. But that laconic demeanour of his, underpinned by a depth of experience that requires no superficial demonstration, is matched in the unobtrusive foundations he has laid for a litany of Shadwell champions either side of the Atlantic.

There had been little obvious induction in Nichols’s Texas upbringing. True, the kind of resources he did usefully inherit can be gleaned from the fact that his father, a construction manager, was self-taught in engineering and architecture. But there was a distant relative in Kansas who had buckskin horses on a cattle ranch. These so captivated Nichols that when he came home, he secretly bought one for $125. He was just 13 years old.

“I was working, plus going to school,” he remembers. “I’d always give my mother money to put in the bank for me. Well, that stopped. She kept pushing me, ‘Why aren’t you giving me money anymore?’ Finally, I had to form a partnership with my brother, held off a little while longer. We finally told them the truth. And they embraced it. My mother, first thing she did was subscribe to every horse magazine in the country.”

Nichols duly focused on equine reproduction at college, only for Vietnam to thwart his veterinary ambitions. (Albeit fortunately the war ended two weeks before he was due to ship out.) Nor was his first job in livestock terribly auspicious, a Kansas veterinarian having engaged him on a pork farm.

“He had dreams of building a big hog production unit,” Nichols recalls wryly. “[But] the old guy that was running the farm realized that if that ever did come to happen, he’d be out of a job. So he fired me.”

I didn’t think anybody would ever employ me that long after getting fired from the hog farm.”

In Nichols’s own words, that meant he “had to settle for the horse business”–initially, with Arabian and show horses back in Texas. “But really I wanted to get into racing,” he recalls. “Show horses are great. But a human being is determining the winner, where in racing the horse determines the winner. That’s the ultimate goal.”

Then he got a break from John D. Marsh in Virginia, who hired Nichols as a farm trainer and manager. That introduced him to the coalface, notably trackwork with John Tammaro–and the kind of grounding, in the problems holding back ordinary animals, that is arguably lacking in those whose education is confined to the equine elite.

“John was a leading trainer in North America when I was with him, but we only had one stake horse in the barn,” Nichols recalls. “He could tell more about a horse galloping on the racetrack than a vet could with an X-ray machine. He’d say, ‘Oh, that horse has got a knee,’ or, ‘Oh, he’s got an ankle.’

“But Mr. Marsh was a very difficult man. We had two really valuable mares. One of them had foaled, the other I thought was going to foal the next night. It was very cold, and we only had one stall with a heat lamp. I sent the maintenance man to the hardware store to buy a Y-socket, so I could put a heat bulb in the stall with the mare that had already foaled. Mr. Marsh heard about it. He called me up there, cussing me from one end to the other. The Y-socket costs 39 cents. I had 40 cents in my pocket. I threw it on his desk and said, ‘I’ll see you.'”

But doing the right thing by a horse means different things in different situations, as Nichols would discover from his next employer. He still views Dr. Robert Leonard of Glade Valley Farm as second only to Sheikh Hamdan among all the horsemen he has encountered.

“A very good reproductive veterinarian, but a horseman first,” Nichols explains. “He raised very good racehorses off very mediocre bloodlines. One time he was gone for the weekend, comes back about 9 o’clock. He calls me up. ‘Come down to barn one.’ So I go down there. ‘What d’you bring this colt in for?’ I said, ‘He’d a big knee, boss.’ He said, ‘Next time you bring a colt out of that field you can wrap a chain around his neck and drag him out with a tractor.’ I mean, he raised a tough horse. But he taught me so much.”

One winter Nichols was driving home to Texas when he stopped off at Spendthrift. He only wanted to see Exclusive Native, but ended up being offered a job. And so began a priceless chapter in his education: learning from great horses, and great horsemen.

For a start there was Steve Johnson, then managing the farm herd. “He was very meticulous in his record-keeping,” Nichols says. “I still use a lot of the things he taught me to this day. He’d have so many lists he had to have a list of his lists.”

But above all there was the boss himself. Putting all his other acumen aside, Leslie Combs was esteemed by Nichols as a true horseman. “I remember the day I had to go in and tell him that Gold Digger had slipped,” he says. “She was carrying a full-sibling to Mr. Prospector. He just looked at me and said, ‘You’ll get her in foal again for me, won’t you boy?’ ‘Sure try.’ Very few people can take news like that.”

As for the stallions, while Nashua was the paragon, the widest spectrum was the one dividing Raise a Native and the notoriously low libido of Seattle Slew.

“I mean, Raise a Native, he actually bred a mare laying on the ground one time,” Nichols says. “He jumped, but hit her low and knocked her down. Slew, he would drive you nuts, because he’d come in and look at the birds in the breeding shed.

“I took one mare up there, we were there from seven till about 11, took a break. Come back after lunch, there till four. Took a break. Come back at seven that night, stayed around until about 10. Next morning I checked her, luckily enough she hadn’t ovulated. Brought her in there, and he bred her like Raise a Native that morning. You just want to shoot him. ‘Why didn’t you do that yesterday!?'”

Wonderfully resonant names, these–yet the challenge Nichols accepted at Shadwell, which soon expanded to nearly 3,000 acres, brought no diminution in quality.

“When the boss came and looked at this property for the first time, with these rolling hills, he questioned me,” Nichols recalls. “Because his farm in England is flat. Dubai is flat. I said, ‘Well, when you run a horse at Epsom, does he run flat or up and down hills?’ He just kind of nodded.”

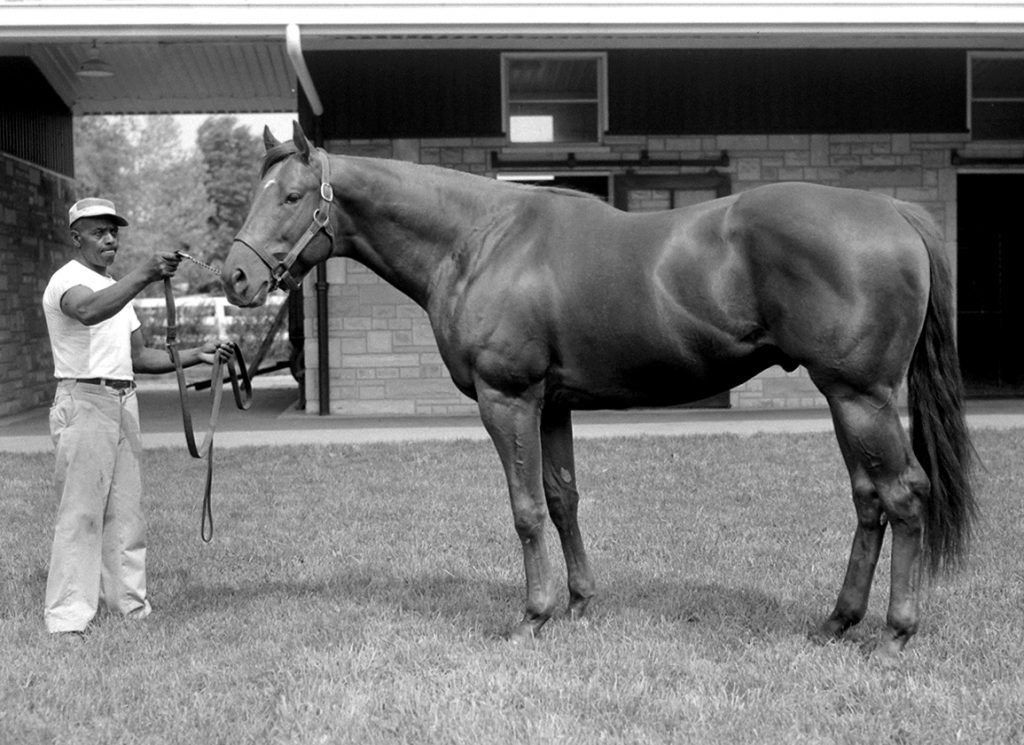

Sure enough, the very first crop raised on the new farm included a Derby winner in Nashwan. He was bred from the great Height of Fashion (Fr), who had been discarded from the royal stud. Nichols gestures to the office wall.

“That’s her, up there: big, long, leggy,” he says. “The boss sent several trainers to see Nashwan as a baby, and all of them said he was leggy. The boss hadn’t seen him yet, he landed and said, ‘Tell me about this Blushing Groom colt. Everybody says he’s leggy.’ I said, ‘He’s not leggy. He’s high off the ground. But a leggy horse has long cannon bones.’ In the paddock before the [2,000] Guineas I asked the boss, ‘Who’s got the shortest cannon bones in there?’ He said, ‘Nashwan, of course.'”

Nashwan was a very obliging animal. The farm’s second Epsom winner, Erhaab, could not have been more different. The Sheikh decided his name–it means ‘intimidating’–the first time he saw him walk out of the barn. With all their top horses, from Sakhee to Dayjur to Jazil, the Sheikh took a very personal hand. And not just in mapping pedigrees, in which he is famously proficient.

One time he flabbergasted his trainer and managers in the winner’s enclosure at Newmarket by asking whether Ta Rib was entered for a Classic in France the following weekend. “Yes, sir, she’s nominated–but it’s only a week away!” The boss nodding, and saying with a shrug: “Gentlemen, next week I’m going to be in Chantilly, and so is this filly. Would you like to join us?” And off he walked, and sure enough Ta Rib won the French Guineas.

And Nichols says it was the Sheikh himself, not jockey Willie Carson as everyone presumed, who discovered the dry strip under the trees when Bahri “stole” a Group 1 mile at Ascot by hugging the far rail. Again, the whole team had heard the boss calmly give the orders in the parade ring with jaws agape.

Sheikh Hamdan… I wish people could get to know him the way I know him. To me, he’s been a father figure.”

But their devotion, measurable in the number of Shadwell employees whose service extends across decades, is rooted in a broader empathy. The Sheikh kept the late Dick Hern in business when–confined as he then was to a wheelchair–even the Queen had moved on. Another of the Sheikh’s most cherished trainers, Kiaran McLaughlin, has likewise been allowed to show that spirit and skill can endure physical challenges undimmed.

One day a reporter accosted the Sheikh at Newmarket and asked how he could persevere with Hern when everybody else had given up on him? He replied: “His body is broken, but not his mind.”

Nichols loved that. As for McLaughlin, he says: “I think he’s phenomenal. For what hand he’s been dealt in life, and how it doesn’t weigh him down. I can’t say enough about how much respect I have for him. A couple of years ago I had a bad accident, shattered both ankles and broke both legs, and was in a wheelchair nine months. I would think about Kiaran. I kept thinking someday I’ll be okay, but Kiaran doesn’t have that hope. His attitude, his mindset, is something you just got to admire.”

The Sheikh understands that the fatalism we learn from horses serves us well away from the track, too.

“Anytime I call the boss to tell him he lost something, he always says, ‘Inshallah,'” Nichols remarks. “God’s will. He takes it very good because he’s a horseman. He knows things happen. When I was at Spendthrift I had like 80 clients, and my phone would ring till midnight. These people, they weren’t horse people. One lady ranted and raved for ten minutes about the fact I hadn’t bred her mare yet, and it was the middle of April. I said, ‘Ma’am, I always thought it would be a good idea to let her foal before we breed her.’ Leaving those 80 clients behind was such a pleasure when you’re dealing with the boss.”

But whatever he left behind, the things he did take with him from Spendthrift became integral to his regime at Shadwell. Above all, a principle that actually brings us full circle. Because Nichols owed that first impression on Sheikh Hamdan to a lesson drummed into him by Leslie Combs.

“He would tell us that if somebody new in the business comes up, and there’s something wrong with that horse, you advise them,” Nichols explains. “Because we need new people in the business. We don’t want to hurt them.

“One night at Keeneland a mare we just put through the ring ruptured her uterine artery. Her gums were white as my shirt, and she just laid down and died. I took her halter off, and was walking around the shedrow, and here comes this young girl. ‘Oh, I’ve come to see my mare.’ I said, ‘What was her name?’ I had her halter, and said, ‘I’m sorry, she just blew her uterine artery.’ She said, ‘Oh my God, my husband’s going to kill me. He forbade me to come out here and buy a horse.’

“I called the owner. ‘Nope, a deal is a deal. Hammer fell. It’s her horse.’ So, I go up to the ring to find Mr. Combs and explained what had happened. I said, ‘Can you call the owner, see if you can persuade him to let this go by?’ He said, ‘Won’t do any good. He’s a jerk. But tell that girl to come out in the morning, 10 o’clock.’

“We go in his office and he’s very apologetic. He said, ‘You paid $10,000 for the mare, right? Go out and see that lady out there.’ We called her Miss Judy. She did all the stallion stuff. ‘She will give you two seasons in West Coast Scout. He stands for $6,000, and she’ll sell them for you and give you the money.’ So she made $2,000 off the deal. That’s the kind of man he was.”

Combs was a famously colourful character. Sheikh Hamdan’s understated exterior, even after all these years, remains rather inscrutable to most of us. As such, Nichols has a privileged insight into a patron who has long assured the breed a historic legacy.

“He’s an incredible man,” Nichols says. “He’s done so much for me and the people at Shadwell. I lost my father when I was 18–and he was my best friend. Sheikh Hamdan… I wish people could get to know him the way I know him. To me, he’s been a father figure. Sometimes like a big brother. Sometimes like a friend.

“He’s always the boss, but he’ll sit around here and we’ll talk just like you and I are talking. In a lot of ways, he’s like my father. I think, outside of my father, he’s the best friend I’ve ever had. My father used to take me hunting. Sheikh Hamdan takes me hunting. I’ve been afforded to do things that kings and queens can’t do.

“He’s very relaxed. There’s not ever any pressure. He knows that as long as he takes care of his people, his people will take care of his horses.”

And that’s just what Nichols has been doing for half his life. “If I can last another few months, I will be 70 years old and I’ve worked for the boss 35 years,” he says. “I didn’t think anybody would ever employ me that long after getting fired from the hog farm.”