TDN is proud to partner with the Keeneland Library and the Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries in a very special new collaboration: the Keeneland ‘Life’s Work’ Oral History Project, a series of filmed interviews by TDN columnist Chris McGrath with significant figures in the Thoroughbred industry. The second of these, with John Phillips of Darby Dan Farm, appears here.

by Chris McGrath (15-minute read)

(Click the link below to listen to this as a podcast.)

His grandfather’s greatest achievements, on the Turf, were all about looking outward; about opening minds and dismantling boundaries. Listening to John Phillips, however, you realize that the impetus for the whole adventure–for the mutual enlightenment, either side of the ocean, achieved by sending Roberto and Ribot in opposite directions–could not have been more definitively American.

And off he went, with a ridiculous notion that some American could just pick out one horse, go off to Europe, and actually win the English Derby. But that was Grandfather.”

Because as Phillips says himself, the story of John Galbreath might have been written by Horatio Alger. A kid raised in a large, poor family in the Ohio back country, whose dynamism and imagination generated a fortune from the steepling transformations of postwar real estate. Happily, as it is, the man charged with sustaining Galbreath’s legacy at the storied Darby Dan Farm proves no mean Alger himself, as reflective as he is eloquent.

“Grandfather was very proud of being an American,” explains Phillips. “That notion of rugged individualism. And if you studied his family–his uncles, his father’s father, and the like… classic Americans going all over the country making fortunes, losing fortunes, [with] a very entrepreneurial, ‘go for it’ attitude. He was never afraid of failure. Some things did fail for him, but he never looked back.”

Sure enough, Galbreath was equally at home with all ranks of society, from farmers in their fields to the boardroom. And it was his faith in American values that prompted him to hire Branch Rickey–the man who brought Jackie Robinson to Major League Baseball–to run his Pittsburgh Pirates.

“He felt that the United States needs to be a meritocracy in everything we do, including sports,” Phillips explains. “So although Branch Rickey was past his prime, it did set the tone for the Pittsburgh Pirates. And they ended up recruiting a lot of minority players with tremendous talent.”

One of these, in the rookie draft of 1954, was an African American from Puerto Rico with very little English: Roberto Clemente. Through the turbulent years of the Civil Rights movement, Clemente’s Hall of Fame career became a powerful symbol for Galbreath.

“The relationship really took a decade to develop, because there was a huge cultural gap between a farmer in Ohio and somebody raised in Puerto Rico,” Phillips recalls. “Nonetheless Roberto Clemente became a close friend. He was a very sensitive, very committed human being.”

In 1970, Galbreath decided to name the most athletic of his yearlings, a Hail to Reason colt, for Clemente; and it was the equine Roberto that farm manager Olin Gentry picked out as most eligible to be sent, on a pioneering mission, to Vincent O’Brien in Ireland.

“And off he went, with a ridiculous notion that some American could just pick out one horse, go off to Europe, and actually win the English Derby,” says Phillips. “But that was Grandfather.”

I think his plan was defined by his passion, more than anything else. And he had an undeniable confidence that things will just work out.”

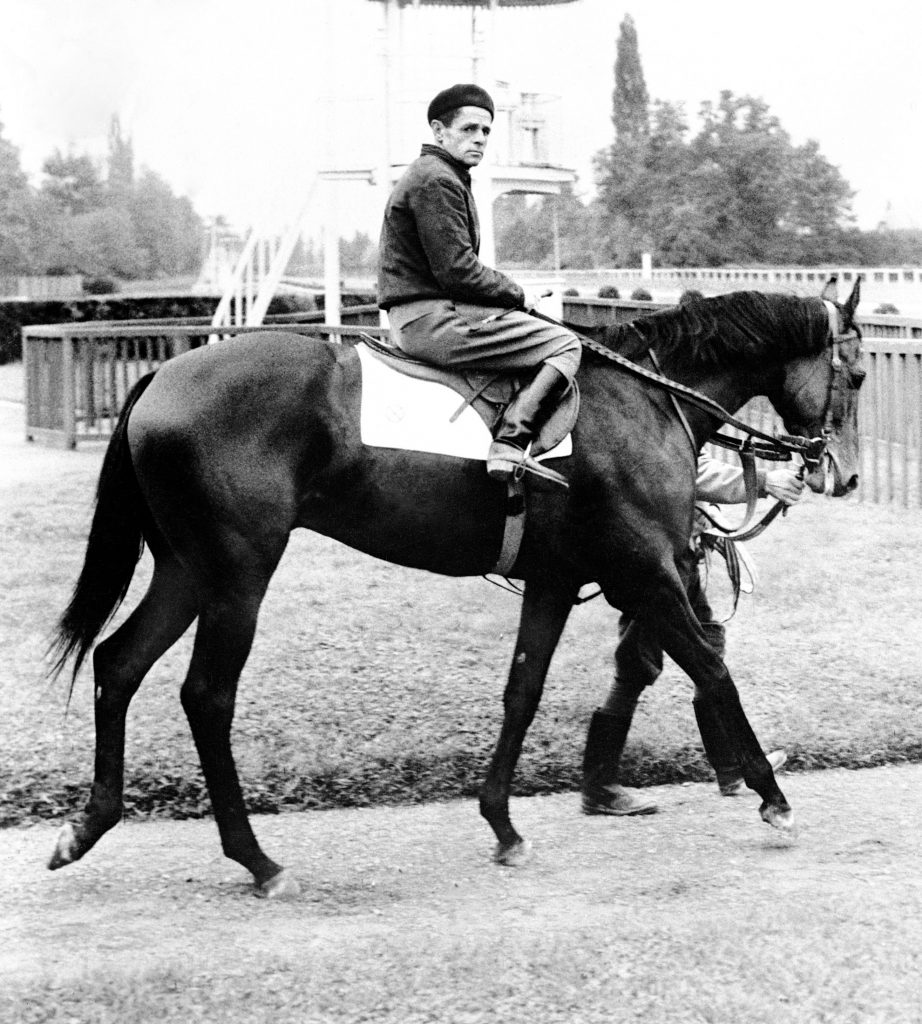

Tragically, of course, Clemente was lost in a plane crash–delivering aid to earthquake victims in Nicaragua–just a few months after his namesake won the 1972 Derby at Epsom. True, Roberto required the very devil of a ride from Lester Piggott, whose defection to runner-up Rheingold for a rematch at York that summer suggested that he, too, believed no other jockey would have got him home. So Galbreath brought over Braulio Baeza to beat not only Rheingold, but also the supposedly invincible Brigadier Gerard.

Nine years previously Baeza had become the first Latin American jockey to win the Kentucky Derby, on Chateaugay, another Galbreath breach of ethnic barriers to elite competition. It was Chateaugay whose exercise rider got it into his head to equal the Pimlico track record when breezing five days before the Preakness. He still finished second, and then won the Belmont, so should probably have won the Triple Crown. Regardless, Galbreath had now become the first man to win both the Kentucky Derby and the Epsom original–historic vindication, as such, for the record sum he had paid for the sire of Chateaugay, Swaps, as the linchpin of his vision for Darby Dan.

“I think his plan was defined by his passion, more than anything else,” Phillips reflects. “And he had an undeniable confidence that things will just work out. So it was crazy money that he paid for Swaps, but his business plan was not what we would anticipate today. It was a different age–the age of the Whitneys, the Vanderbilts, the Firestones; the big, prominent East Coast families, and a few oil families, and the like. So the value was not so much in the horses, as in networking. I think that’s how he looked at it. If he could survive enough, the value would be in the contacts and relationships he made. That was true in baseball as well.”

This tract of the Bluegrass already had a long history, originally surveyed by Daniel Boone and first used to raise Thoroughbreds by a great character of frontier era, Colonel E.R. Bradley. As Idle Hour Farm, it had everything from its own fire engines to a chapel to a railhead.

“Bradley was a classic American story in his own right,” says Phillips. “He’d had all sorts of adventures in the West. He loved to bet on, raise, and race horses, and came here with the intent of producing the quintessential horse farm of the time. He was Irish Catholic, devoted to his religion, and yet had this passion for gambling, enjoyed his bourbon, and started the Fair Grounds racetrack in New Orleans. He had more Derby entrants than anybody in history, and won four times.”

Galbreath bought a first parcel of Idle Hour after Bradley’s death in 1946. And one of the accompanying boons was Gentry.

“Another character,” recalls Phillips wryly. “Very much a gentleman, but he had his Southern values–I’ll leave it that way. His mark is on pedigrees we still have here after so many generations. John Galbreath had a basic principle in almost everything he did: ‘You hire the best people you can, and then let them do what they’re hired for.’ He was very knowledgeable about horses, an excellent rider in its own right, but also understood that he was not doing it day-to-day. That overrides any ego, so he really deferred to Olin quite a bit when it came to matings.”

But it was Galbreath himself who conjured the big-picture, left-field strategies. Two years before Chateaugay’s Derby, he had brought over the dual Arc winner Ribot–no straightforward enterprise, evidently, with Federico Tesio’s widow still smarting on behalf of Italy’s wounded postwar pride.

“As I understand it, Mrs. Tesio was reluctant to have the Americans come in and throw a bunch of money at her husband’s horses, and walk away with the spoils of war,” explains Phillips. “Grandfather understood that and said, ‘Look, don’t sell your national treasure. But you can rent him, at least for a few years. And then he can come back, if you really want him to.’ A lot of people thought it was an insane price. But if I heard Grandfather say it once, I heard him say it a thousand times: ‘Takes the same money to raise a bad horse as it does a good one.’ He believed in quality.”

In the event, Ribot’s temperament proved such that no sane handler would attempt to repatriate him. He would rear up on his hindlegs and chew the beam of his stall. At one point they put up a special barn adjacent to his paddock, which had solid wood fencing, so that he did not have to be walked there. Ribot lived there for all of two minutes.

“And then the groom said, ‘Mr. Gentry, that horse is either going to tear it down, or kill himself,'” remembers Phillips. “So he was let out of his brand-new barn, never to return again. The notion of him returning [to Europe] was just too risky. That, certainly, was the notion Olin Gentry conveyed to all the hands that came to inspect him!”

If I’d have to point to a single event that got me involved in horse racing, it was seeing Graustark at Keeneland.”

From his second Darby Dan crop Ribot produced an extraordinary animal: Graustark.

“When I was 14, Grandfather said, ‘Come on, we’re going to fly down to Kentucky to watch this horse,'” Phillips remembers. “The buzz at the racetrack was phenomenal, you could hear people say, ‘I can’t wait to see him.’ I had no idea who the ‘him’ really was. So I went down, my hand in Grandfather’s hand, for my very first gaze at Graustark. And it was, ‘Whoa!’ Very masculine, a unique color, liver chestnut, totally dappled, very much on his toes–and bold. An unforgettable image. And then the race itself. He was in cruise control, just as calm as could be; and his stride was awesome. If I’d have to point to a single event that got me involved in horse racing, it was seeing Graustark at Keeneland.”

And then, to complete the introduction of the young Phillips to the highs and lows of his ultimate vocation, Graustark broke his coffin bone on his next start.

Besides Ribot, the other European phenomenon brought to Darby Dan was Sea-Bird. In each case, Galbreath was seeking Classic blood. “America had begun to focus on speed,” Phillips reasons. “And that carried on with the body types that guys like Wayne Lukas became attracted to, much more a Quarter Horse conformation and look. Grandfather thought winning the Belmont was equally as fantastic as winning the Derby. And that Europe was the best repository of the genetics to accomplish that.”

Sea-Bird’s son Little Current confirmed as much in 1974, as another Triple Crown winner manqué: after a luckless Kentucky Derby run that ultimately caused the safety limit to be reduced, he won both other legs by seven lengths. But Roberto’s sire Hail to Reason had already shown how bloodlines could transcend racing disciplines, giving Galbreath a second Kentucky Derby in 1967.

“They had called the National Guard out that day because there were some brutal social issues, riots, a lot of unrest,” Phillips recalls. “And there was a threat that a bomb was going to be placed in a grandstand. And what made it even stranger, even more eerie, it was a totally foggy day. In the grandstand, you just saw shadows going by on the backside. And then out of the mist, it’s Proud Clarion and everybody’s scratching their head: ‘Who? Where’s Damascus?’ He shocked everybody–including ourselves.”

I wasn’t a very good lawyer, to be truthful. If I could have remembered my law like I can pedigrees, I probably would have been on the Supreme Court. But the fact of the matter is I wasn’t looking forward to getting up in the morning as much as I do now.”

Gradually Galbreath and Gentry developed their own dynasties, sometimes planning matings specifically to pair a resulting filly with another Darby Dan stallion. And the process became so organic that, in 1985 alone, Roberto sired both Brian’s Time, later a potent sire in Japan, and turf champion Sunshine Forever out of Graustark daughters of the Galbreath foundation mare Golden Trail; and also Dynaformer, later an important sire himself, out of a granddaughter of Golden Trail by Graustark’s brother His Majesty.

For Galbreath’s passion was not just the winner’s circle, but the patient cycles of getting there. “Now, that challenged him later,” Phillips admits. “In the ’80s it almost caused the death of Darby Dan. But it was a beautiful process.”

By the time of Galbreath’s death, in 1988, the old school of home-farm breeding underpinned by purse money was being outflanked by a market surge driven by global investors like the Maktoums and Coolmore. You could still seek sanctuary from soaring stallion fees in your own bloodlines, but rival farms were increasingly predicating their business plans on the commercial market.

Phillips himself had by then renounced a legal career. “I wasn’t a very good lawyer, to be truthful,” he says. “If I could have remembered my law like I can pedigrees, I probably would have been on the Supreme Court. But the fact of the matter is I wasn’t looking forward to getting up in the morning as much as I do now.”

For the Graustark dazzle had never dimmed, and it ultimately fell to Phillips to supervise the farm’s transition. A consultant had come in and concluded that the whole thing was crazy, and that the horses should be dispersed. While Phillips refused that surrender, he did recognize the need to dig in for a more sustainable model.

Today Darby Dan offers a roster of a dozen commercial stallions alongside sundry other services. “We had 70 mares, only four of which were not ours,” Phillips recalls. “Now we have 150, 130 which are not ours. So it’s a different program. We run the gamut. But commercial operation allows us to continue our participation in the industry, for which I’m really blessed.”

Soaring Softly, then, represented an important symbol as inaugural winner of the GI Breeders’ Cup Filly & Mare Turf in 1999. She extended a family cultivated by the farm for generations, at a time when Phillips had lost not only his grandfather and uncle, but now also his father.

“So she was a real key horse at a watershed moment,” he says. “Just a signal, I think, to the family and the industry: ‘Hey, we’re still here, and we love it, and we’re going to go on with it.'”

So at 67 years old, I’m still planting trees. And still hoping that those pedigrees carry on, not only for decades, but for generations. And I love it, that this is what my epitaph is. It is this ground, and these horses.”

But the filly who had truly branded the new regime was Memories of Silver, who in 1996 broke the track record in winning one of six GI Queen Elizabeth II Challenge Cup trophies displayed in the old mansion at Darby Dan. Besides anything else, it was a trademark farm pedigree: by Roberto’s son Silver Hawk, out of a Little Current daughter of Java Moon, who was in turn by Graustark out of Golden Trail.

“A wonderful, wonderful horse,” says Phillips. “There’s almost no words, because she came along at a time that was critical for our family, and she’s just beautiful. Takes your breath away. So well put together, such pretty lines, and such a kind disposition.”

When Memories of Silver tried her first stakes at Saratoga, after requiring four starts to break her maiden, Jerry Bailey was kindly released from a commitment by Elliott Walden, albeit in some perplexity.

“About two weeks before the race, Elliott was at the gap at the Oklahoma and here comes Jerry Bailey on Memories of Silver,” Phillips recalls. “And he says to Elliott, ‘Watch this.’ And he goes out and does five furlongs in :57-and-change. Jimmy Toner, the trainer, who’s a great friend and wonderful guy, was going ballistic. And Jerry Bailey just comes by and just gives Elliott a big smile.”

After she won, Phillips sat on the deck at Saratoga and called his mother. It was a memorable lift for the whole family. And it was on the day of his mother’s funeral, 12 years later, that Memories of Silver delivered a gray filly by El Prado (Ire). Phillips thought how happy his mother would have been: she always liked to put her two dollars on a gray. And that was another multiple Grade I winner, Winter Memories.

Between them, mother and daughter have qualified their family to produce a number of hugely lucrative sales, and so helped to keep the whole Darby Dan ship afloat.

“I don’t know how some people really do it, quite frankly,” says Phillips. “We don’t have an oil well in the backyard. I’m not faulting anybody that does, I wish I did. But it’s got to be a sustainable operation: both the farm operation, and the family horses. And that’s sometimes challenging to do. But we started off with a great platform of the broodmares that my grandparents accumulated 70 years ago, and we’ve managed not to mess it up too badly.

“The fact of the matter is we are just stewards. So I plant trees here, and the staff will tell you I’m crazy about those trees, the shade of which I’ll never experience. But somebody will. Because Colonel Bradley planted trees, and those who went before him took care of the land too. So at 67 years old, I’m still planting trees. And still hoping that those pedigrees carry on, not only for decades, but for generations. And I love it, that this is what my epitaph is. It is this ground, and these horses.”