by Sue Morris Finley (14-minute read)

(AUDIO: click to listen to this story.)

Of all the terrible things that mankind has inflicted upon one another, there is none so terrible as war.

Estimates of the total number of people killed in war in the history of the world range up to a billion lives, and for the combatants, oftentimes just surviving the conflict seems like the goal. But of course, too many people come home from combat only to find that they cannot leave it behind.

Though she served in the military for 21 years, Tei Pascal can pinpoint the exact period during her service from which her post-traumatic stress stems.

“During my 21-year career, I had five deployments, and one of those deployments was to Kirkuk, Iraq,” Pascal recalled. “And at that particular time we had a lot of mortar attacks. The mortar attacks would happen almost daily; I would say five days out of seven. At the time, I wasn’t really worried because I knew that I was trained properly and we had good camaraderie in my unit, in my squadron.”

It wasn’t until she returned home that she realized what a toll those daily attacks had taken on her.

“When I got back from Iraq, I lived in Florida, and so here I am one afternoon with my son, and we’re outside, and a car alarm was triggered by a thunderstorm. And I found myself taking cover. And it really scared me because I didn’t know what was going on. I felt as if I was back in Iraq. I felt as if time kind of stood still.”

In 2013, the Veterans Administration released a study which showed that 22 veterans a day were committing suicide.

The 44-year-old Pascal is well-dressed, and exudes an air of calm. She’s sitting in a courtyard at the Bergen Equestrian Center in Leonia, New Jersey, the riding facility that is home to the Man O’ War Project. Pascal rests on a stool near an L-shaped barn housing a dozen or so horses; horses, she says, who gave her her life back.

In 2013, the Veterans Administration released a study which showed that 22 veterans a day were committing suicide. That means that just over every hour, a veteran takes his or her own life. While vets make up seven percent of the population, they account for 22 percent of its suicides–a suicide rate over three times the average for other Americans.

At the heart of their struggle, of course, is PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder. Especially common in combat veterans, PTSD is a psychiatric disorder that occurs in people who have experienced a traumatic event or a long period in which they felt trauma. It can cause flashbacks, nightmares, anger, fear, estrangement, and a lack of trust.

It was that lack of trust that Pascal says was the obvious sign that something was wrong. “What I found was all of a sudden I was on edge,” she said. “I didn’t trust people. I was constantly looking over my shoulder. I went through moments of isolation and then finally moments, as the years went on, of depression. And it wasn’t until 2017 or 2018 where I finally decided, ‘Okay, I can’t do this on my own. I need to see someone.’”

In a country that makes a public show of praising its veterans, at ballgames, in airports, and in signs and banners thanking them for their service, it is difficult, if not impossible, to find effective treatment for PTSD. It is especially frustrating to the people on the front lines of the mental health battle that more real assistance for America’s veterans is not a priority.

“Sadly, the military, the Department of Defense, the VA, the federal government has not done enough to understand the basis of psychological injuries of military experience in combat as could have been done,” said Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman, the Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University.

Lieberman manages the largest psychiatric department in the world, with over 700 doctors working under him, and has taken a keen interest in the Man O’ War Project. Concerned with the military’s mental health crisis, he is dedicated to raising awareness, and finding alternative treatments for PTSD.

“This is not global warming. This is something which should be readily solvable but it’s not because there hasn’t been funding of the best scientific minds to do so.” –Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman

“There are a lot of treatments that are being used, but they’re not really very effective,” he said. “And it’s doubly shameful because of the fact that this condition–from the standpoint of how scientifically challenging or difficult it may be to understand–should be solvable.”

Lieberman stresses that last point.

“This is not global warming. This is something which should be readily solvable but it’s not because there hasn’t been funding of the best scientific minds to do so.”

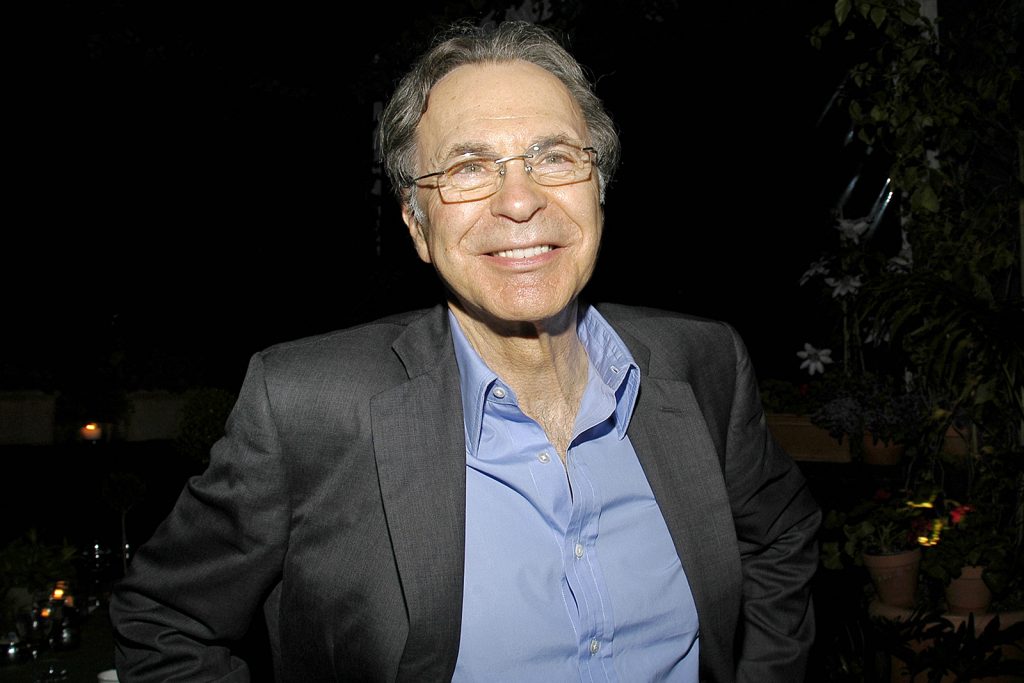

Into this breach, said Lieberman, stepped Earle Mack.

Mack, well-known to the Thoroughbred racing industry as an owner and breeder, is a businessman, philanthropist, and former U.S. Ambassador. He is also an Army veteran.

“Earle Mack said, `I have an idea. I’m not a scientist but I have an idea and I think it’s worth testing and I’m willing to put my money where my mouth is.’ And so, he did,” said Lieberman.

Mack has long been involved with Thoroughbred retirement, funding projects at the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation, which pairs prison inmates with racehorses in rehabilitative programs. But he said as he looked at that program, and the many others pairing racehorses with troubled teens and veterans with PTSD, he found himself wishing that the results they reported were more than anecdotal. It occurred to him how beneficial it could be if they were, instead, proven.

At the time, Mack had a friend, Dr. David Shaffer, who was a professor of child psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Shaffer was working on the problem of youth suicide, one of the leading causes of death for young people. Mack convinced him that if they could understand and develop the science for treating the PTSD in veterans that so often leads to suicide, treating young people would be equally understandable.

Shaffer was on board.

“We don’t do nearly enough for our vets,” said Mack, who went through the Army’s officers’ training program, active duty and eight and a half years in the active reserve. “I saw the suffering that our vets go through. I saw the frustration. It always bothered me. I think there’s lack of organization and of funding by the VA, and that discourages people from going there for help. To me, it’s unforgivable the way America treats its vets.”

Mack put $2 million of his own foundation’s money up, raised another million from the outside, including a $200,000 donation from The Jockey Club, and started the project, which uses former Thoroughbred racehorses in trust-building exercises with the veterans.

“Earle was not the first one to come up with a theory that horses could help people with PTSD,” said Lieberman, who works closely with the project’s co-investigators, Dr. Prudence Fisher and Dr. Yuval Neria, both leading psychiatrists in their fields. “Other people had been working on it. But what he said to me was that nobody had ever done the science. Nobody has ever done the studies. Nobody has ever done what it would take to make this something that is not just anecdotal. `Oh, I hear this is good for horses. I hear that so-and-so farm has done some good things.’ But to put an official stamp on it from some of the smartest people in the world to say that this is in fact effective and a good treatment, for not only just soldiers but anybody suffering from PTSD, well, that’s the key.”

To put an official stamp on it from some of the smartest people in the world to say that this is in fact effective and a good treatment, for not only just soldiers but anybody suffering from PTSD, well, that’s the key.”

Anne Poulson is a soft-spoken, thoughtful attorney who is the former president of the Virginia Thoroughbred Association and chair of the Virginia Racing Commission. She grew up riding, and now serves as president of the Man O’ War Project.

“As many people know, Ambassador Mack is very involved in Thoroughbred aftercare and he had witnessed, as many of us have, these wonderful programs that are out there where you have horses and veterans getting together and there are tangible, feel-good moments with some sort of a change, but there’s no way to measure that change beyond anecdotal stories, and no science behind it.

“The idea was, let’s find out what the science is. Let’s do a scientifically rigorous study of horses and veterans. Let’s get a methodology behind this, a protocol that can work and understand why it works. Columbia University didn’t have any experience with horses. They did, however, have a world-renowned psychiatric department with extensive experience in military mental health, combined with expertise in the field of suicide. In addition, they have one of the world’s best trauma and PTSD facilities directed by Dr. Neria, a decorated combat veteran himself. So they were very interested in the concept.”

First, she said, Dr. Neria and Dr. Fisher spent a year and a half traveling the country, looking at different programs and learning about equine-assisted therapy. By 2016, they had developed an eight-week protocol with pilot groups, produced a 100-page manual as a guide, and started a rigorous screening process for applicants.

“The program itself really is all about putting science behind these anecdotal stories,” said Poulson. “We know that it works, but there needs to be some uniformity, some methodology, and I think in order for these programs to become mainstream, which is really the goal, there needs to be a proven program with trained professionals, including mental health professionals, who work with the veterans. If everybody is doing something differently, even though it looks like it’s working, we can’t really know what’s working or quantify the results.”

Two years later, they are on the cusp of doing just that.

Next month, the last group of participants will complete the program. The vets are given MRIs before they start the program and again at the end to record changes in the brain. Those results will be consolidated along with the detailed clinical data and the formal study published.

But already, the anecdotal results are clear.

“The results look very encouraging,” said Lieberman, “meaning that there does seem to be very significant clinical improvement in terms of a reduction in symptom severity for veterans undergoing treatment.”

What’s more, he said, the reasons why make sense.

“When you deal with people, you’re always sort of trying to feel out, `How are they? What do they think of me? What am I saying? Are they good? Are they bad? What do they want? What do I want?’” Lieberman said. “Horses produce a safe relational engagement, more so than any pet or even any person. And, that produces a kind of a transient relaxation in the hypervigilance and the noxious emotionality associated with the traumatic experience that the individual underwent. And, with the kind of repeated administration on this, it allows for the dissipation of the noxious, intensive, emotional component to the memories of traumatic experience that has been undergone.”

And the perfect horses for the program, Poulson said, are not just any horses, but retired Thoroughbred racehorses, due to their intelligence and the traits they share with veterans. They had a short, intense career, and need a job when it’s over.

“Horses are unique in that they are very much like the veterans themselves,” she said. “They are hypervigilant, they’re creatures of prey, they very much have a mission in life. They enjoy a job. They like a purpose. When vets are deployed into active service, they have a mission, they have a goal. And, daily, that is the way that they live their lives and they come home and all of a sudden that mission is gone, but the mission mentality is still there. So they too are looking for what their next step is, what their next goal is. ‘What is my next job?’”

The horse, she said, is like a big mirror. “If you walk into a stall and you’ve had a bad day, that horse is going to catch that vibe and they’re not going to want to work with you that day. They’re going to say, `Come back tomorrow.’ The good news is, they’re not judgmental and the next day they’ll go about their job if you come back with the right attitude. And the veterans learn from that.”

“I think that interaction, the whole building of trust, is the key to the program,” she said. “I think the other thing that’s very helpful to the veterans themselves is, in this program, they’re not asked to relive their trauma. They come out here, they exhale in this beautiful environment and then they get to do something very hands on. They get to build this relationship and they are able to take that experience and transfer it to their human relationships. So it makes them function again because they can transfer these life lessons and skills to family, they can transfer it to work, and to their everyday lives. It’s quite a remarkable and rewarding thing to see.”

Pascal agreed, and said that many veterans are emotionally unable to participate in traditional group therapy, both because they don’t want to relive the trauma, and because of the stigma of having a mental health issue.

“Oh my gosh, you didn’t talk about it at all,” she said. “You didn’t talk about it because in the military there’s a stigma if you talk about your mental health in a negative light. And that stigma is, `Okay, well, what’s wrong? You can’t do your job, so let’s set you over here or let’s put you in this category, and we’ll move everybody else along.’ And so no one wanted to be labeled as that person, and that included me,” said Pascal.

“As a mother, as someone that was viewed as highly respected in my field in the military, I felt as if I always had to be superwoman. I always felt as if I had to keep it together, to carry on with the mission, both personal and professional. So I absolutely didn’t talk about it. It was `Okay, let me put my head down and barrel through and deal with it the best way that I could.” And I did that for years. Oh my gosh. So many years. And then finally I got to a breaking point to where my body was like, `Enough is enough.’”

The Man O’ War Project…gave me the ability to walk through life and not worry about who’s behind me–to live fully. And that’s something I’m forever grateful for.” –Tei Pascal, U.S. Air Force Veteran

The program changed her whole life, said Pascal, who bonded with one particular Thoroughbred. “We kind of needed each other. And in the end, I believe that’s exactly what it was. He needed something from me, and I needed something from him. And what I needed from him was the ability to let go and surrender so I could start to build. And that’s what the Man O’ War Project did for me. It gave me the ability to walk through life and not worry about who’s behind me–to live fully. And that’s something I’m forever grateful for.”

In the end, it will be Mack’s insistence upon documenting the science of the project that was the card to play. When the study is published, most likely later this year, the program can be replicated across the country. It will also make the project eligible for grants from a number of organizations, including potentially the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the National Institutes of Health.

“The model, which is tested, can be distributed,” said Lieberman, “made available to other facilities that want to provide treatment, to veterans organizations that want to simply find a way to have the treatment enacted in conjunction with their mental health care facility, or to equine-assisted therapy programs seeking a proven, effective protocol.

“Earle didn’t discover the idea but he had the good sense to go to a place where there was expertise that knew how to vet the idea. And, what happens all too often is, you have people who believe in something either because of their own personal experience or because they have some kind of ideological or advocacy motivation and they say it works.

“I know it works,” Lieberman said. “But taking it at face value, that’s not the way medicine and science works. You’ve got to prove it. And Earle was willing to submit this hypothesis to rigorous testing in the form of a clinical trial and that makes all the difference.”

At the end of the day, said Lieberman, we weren’t meeting our obligation as a country, and Mack decided to fill the void. “The point is that this is a very simple, intuitive therapeutic process that the government hasn’t seen fit to deal with sufficiently, and civic-minded people are stepping in.”

Mack’s life has been one of service to his country, of philanthropy, of giving back. But if he’s right about this, and it appears he will be proven so, easing the suffering of PTSD in vets and in others won’t just be the achievement of his lifetime; many would consider it one of the greatest achievements ever.

“Think of the number of racehorses we can save,” he says.

Think of the number of lives.