By Chris McGrath

(To listen to this story as a podcast, click the play button below).

Nobody, we keep telling ourselves, remembers a time quite like this. And that’s true even of John Williams, who has seen just about everything in our business. But he did once experience something pretty similar—worse, if anything, strictly in terms of the springtime routines of a stallion farm. That was when Caro imported a wildly contagious venereal disease from France to Spendthrift, and the Department of Agriculture wanted to put a chain on the gate.

Williams imagined that he’d already fulfilled his most stressful task, in boarding a plane to Paris with a cheque for $4.2 million in his pocket. After bringing Caro to Kentucky, however, the world’s premier stallion roster could only be kept in business if everyone in the breeding shed wore surgical hoods, gowns, boots and gloves. Every square inch was disinfected and quarantined. As it happens, Williams gave his time to this project long before the current crisis. But however rare the precedent—whether in the quality of horses and horsemen, or in the dramas that colour their lives—you will find some guidance in the tapestry of a life too rich to be adequately unstitched here.

Perhaps the best measure of his wisdom, integrity and charm is the single compliment that might overcome his dread of flattery. For his regard for the dignity of the office is such that Williams would be pleased, mighty pleased, still to be simply acknowledged as a good horse-groom.

“Bill Haun instilled this in me,” he says, recalling one of the mentors of his Maryland youth. “That the most important person to the horse is not the trainer, not the owner, but the groom who lives with him. On the racetrack, I loved being with some more than others; but I loved being with all of them. I’ll never forget rubbing a horse called Tara Host. They claimed him at Monmouth Park. And I’m coming back with the groom leading my horse to another barn, and trying to get him to understand: he can’t blow the dirt out of his eyes, he doesn’t like it, and all the things I knew about him, as we’re going back with this bridle in my hand and crying because I’d lost him.”

That the most important person to the horse is not the trainer, not the owner, but the groom who lives with him.

–John Williams

The snowy-haired septuagenarian before us remains in tandem with that young groom not just in brightness of eye or spryness of demeanour. He also has the constant prompt of a photograph, at home in Versailles, preserving his first ever visit to the winner’s circle at the age of 24.

“Let’s see,” he says. “This is April 5, 1966. The winner’s circle at what is no longer a racetrack. Bowie, Maryland. With Edgar Lucas, the owner of Helmore Farm. I was working for this wonderful horseman Billy Haun. And here I am, with a mare called Compass Rose. Can you see how proud I was, to be standing in that winner’s circle? I mean, you’d think we just won the Oaks. And Mr. Lucas, look how happy he is to win a $5,000 claimer. This is how much we loved it, even at that level.”

The young man in the picture had no immediate background in horses—though Williams is still maddened that the old equine remedies collated by an Irish grandfather he never knew, who came over with a draft of coach horses for a wealthy family in Philadelphia, were incinerated on his death—beyond a father who couldn’t wait to close the barbershop in time to catch the daily double at Pimlico.

Yet Williams had only completed his first semester at the University of Maryland when switching his education to Pistorio Farm, outside his hometown of Ellicott City. Here he was blessed to encounter a veterinarian as communicative as he was sage, Dr. Irwin Frock.

Admittedly his first racetrack employer did not prove quite so exemplary, but the time and place were propitious: that was the year the memorable Horatio Luro, his hat tilted just so, came to town with a colt they reckoned no more than 15.2hh.

“He’d need elevator shoes to be 15.2,” declares Williams. “He was just a little piece of a horse. But all of us that have ever been in the Thoroughbred business and weren’t comatose know the influence this horse has had on our breed. I don’t know that there would be a horse in a starting gate anywhere in this world today that can’t trace some of his lineage to that little 15.1 colt I saw try to get his way through a jammed door at the backside of Pimlico racetrack in the spring of 1964.”

Fortunately, Williams was soon taken on by Haun. A difficult man, evidently, but he had absolute respect for the horse and demanded unstinting attention to detail from his staff. And, in turn, it was through Haun’s patron that Williams got his big break. Lucas had just bought an annex to his farm and, “preposterous” as it still seems to him, the young college dropout was asked to manage it. As Williams recalls, “instead of being petrified I just jumped at the chance.” He learned as he went along: knew when to call on the advice of old horsemen like Tommy Harraway or Bill Ballinger; and knew, most of the time, when to roll with the fearless energy of his youth.

Best of all was that Helmore raised horses not to sell, but to carry the black silks with white stars. There was, however, a fateful exception—a yearling colt Lucas decided to sell at Keeneland. Williams prepped him as though for the racetrack, hand-walking him up hill and down dale, and the outcome of his diligence caught the eye of the trailblazing consignor Lee Eaton. He urged Williams to come to Kentucky; and so, too, did Tyson Gilpin after seeing how Williams handled a couple of stallions sent by a client to Helmore. Williams was reluctant to leave his home state, but an interview with Olin Gentry proved too tempting; and while that job eventually went to the Spendthrift manager, Williams duly filled the resulting vacancy there instead.

Oh, those Spendthrift years! How on earth to siphon such intoxicating names into the cold vessel of a few sentences? It was 1976, the cusp of the boom that would transform the stallion market; and Leslie Combs was all set to ride the wave. Because nobody got the better of Combs in a deal. (That’s why Williams has a dollar bill framed on his wall. He bet his boss that a particular yearling would bring a million, and Combs staked a dollar that he wouldn’t. Presumably he was happy enough to lose the wager but Williams, as “the only human being that ever beat you out of a buck,” made him sign the banknote.)

“He was the father of modern-day syndication,” Williams says. “He had tremendous clientele; and there was a good balance there, too, because many of them were racing people. But he was truly a commercial horse breeder. There was a cartoon with Leslie Combs standing in front of a conveyor belt with all these little horses going down it. That was his game, and he was a master at it. I’m sure a lot of the places steeped in tradition, like Greentree, looked at Spendthrift as a blue-collar farm. But he brought so many people into the business. He brought them to the party and made it fun.”

That was his game, and he was a master at it…he brought so many people into the business. He brought them to the party and made it fun. –John Williams on Leslie Combs

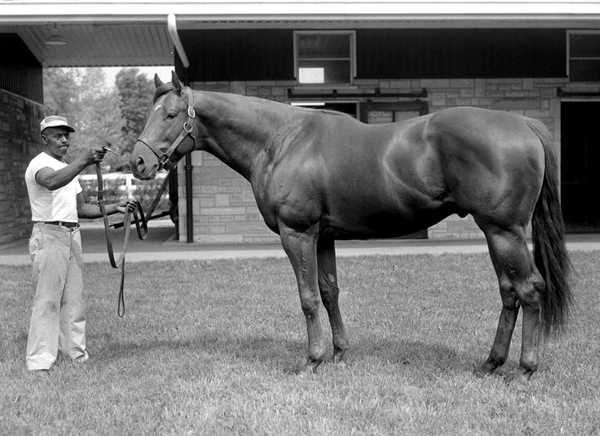

Even the bricks and mortar of the U-shaped stallion barn showed that Combs, and in turn his son Brownell, meant business of a different kind. They called it the Nashua Motel, for the signature acquisition Combs had made to head a roster that kept expanding in both quality and quantity. There was Raise A Native, of whom it was said that he could run over a puddle and leave it dry; there was Exclusive Native; and Prince John; and Never Bend; and Pretense; and Sham. “Poor Sham,” says Williams, “who all he did was look at that big, red rear end of Secretariat through that gruelling Triple Crown season.” And so it went on: names that bestride the modern Stud Book; but flesh and blood, feed and foible, to Williams.

And then there was Nashua, his paragon: Maryland-bred, of course; the benchmark against which Williams has measured every champion since, and invariably found them wanting. Though the horse was already 26 when Williams met him, even then he was immaculate: balance, bone, perfectly round feet. And so hardy. Eddie Arcaro once told Williams how Nashua threw in one of his periodic stinking workouts before the Wood Memorial. He was jogging back, wondering what to say to Sunny Jim Fitzsimmons. Before Arcaro could open his mouth, the trainer gestured simply to go and work again. This time Nashua put in a bullet—and of course won the Wood three days later. “That’s how durable he was,” says Williams. “If a trainer did that now, they’d probably lock him up.”

He is convinced he won’t see the like of Nashua again. “Well, as I said, I’m just a groom,” he says. “I’m not a scientist so I can’t give you proof. I can only give you a perception that I have. But if you were on the racetrack in the early ‘60s and saw the bone that we had, the feet that we had, very rarely would I hear about quarter-cracks or bruised feet or anything like that. Now we’re seeing delicate bone, small or shelly feet, low-slung heels, long toe. What’s causing that? My guess is that we had such a wide variety of pedigree available to us. I mean, we had Man o’ War, which has disappeared. We had the Nasrullah line, we had Pharamond. We had so much we could draw from back then.”

In an era meanwhile saturated by Northern Dancer and Mr Prospector bloodlines, thanks partly to huge books, Williams now sees putative champions who can’t put together 14 starts—never mind the 14 Grade I wins of the 11th Triple Crown winner.

Affirmed was raced by Patrice and the late Lou Wolfson, who became such loyal friends that when Williams eventually left Spendthrift (uncomfortable with the Wall Street flotation of a roster then exceeding 40 stallions) they insisted that their mares would go with him. Affirmed, of course, was by Raise A Native’s son Exclusive Native—each, in turn, having raced for Harbor View Farm. Exclusive Native started out at $1,500, while Wolfson sold Affirmed’s dam for $5,500. As Williams says, there’s “lightning in a bottle” for you.

The uncertainties of the business were distilled by the other Triple Crown winner syndicated, back-to-back, by Spendthrift—responsible, jokes Williams, for whitening his hair in a single spring. He recalls ringing Mickey Taylor after Seattle Slew’s first week in his new job.

“‘Mickey, we have a problem.’ ‘What is it?’ ‘He doesn’t like girls.’ That’s a $12 million stud horse. They don’t want to hear that. After a pause, he said, ‘Well, I know he’s in good hands.’”

So began the long, arduous process of awakening the champ’s dormant libido.

“We finally got him to where he would show some amorous attention to a 28-year-old Count Fleet mare I had brought down from Maryland,” Williams recalls. “She wouldn’t have had very many guys on her dance card. This was not a very pretty mare but Slew kind of thought, maybe. When we’d book a mare, we’d bring old Fleet Flight down there to the breeding shed, too, and he would feel real happy when he saw her. At the right moment, we could move him over to his assigned mare and he would cover that mare. When he came down, he was so mad. But that’s how we had to keep him going.”

There were other tricks Williams remembered from the old days in Maryland. Sometimes he would effectively treat this dual Horse of the Year as his own teaser: the staff would have to drop everything when the holler came that Slew was ready, and get that mare bred wherever the inspiration had visited him: out on a hill, out in the rain or snow.

Because if he couldn’t rely on Slew, he could rely on his crew. True to form, in fact, that’s what Williams prizes above all the other things he has achieved in the business. In his first month as Spendthrift manager, it had been necessary to cull staff by the dozen. It was a tough time; they shot the mailbox off the post in front of his house. But he needed people animated not just by a wage, but by the privilege of working with these beautiful animals.

Fortunately there was a cherished core, the likes of Clem Brooks and Buster Gordon, but Williams needed fresh blood. He spread a net through Maryland, Virginia, Europe; above all, through Michael Osborne’s Irish National Stud program. And he hired women, too. The fact that they hadn’t previously been permitted to work with the horses struck him as a shocking waste of natural empathy. And how proud he is, now, to see some of the pimply kids who started out with rubbing rags at Spendthrift today excelling as breeders in their own right.

“Yeah, I’ve a kind of parental pride in those people,” he says. “Maybe I helped them a little bit, but they helped themselves. All they needed was the opportunity. Now I just hope that they’re mentoring like-minded young people. I don’t see quite as many that really want to be with the horse the way we did then. I see them wanting executive positions, air-conditioned offices, doing deals. I mean, none of us go into the barn and say, ‘Ah great, I got 25 stalls to muck out. And four of them with nurse mares in.’ No, none of us felt that way. But we wanted to be with the horse.”

Yeah, I’ve a kind of parental pride in those people. Maybe I helped them a little bit, but they helped themselves. All they needed was the opportunity. –John Williams

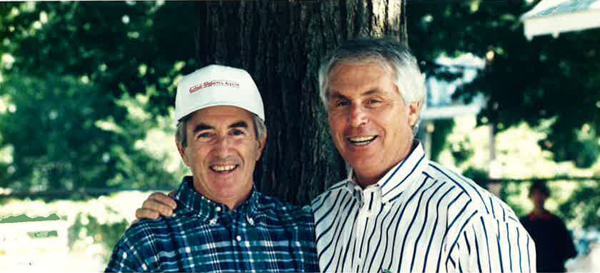

Sure enough, he is certain that the “Flying Start” program—Williams was humbled to be named Osborne’s successor as trustee—will prove Sheikh Mohammed’s greatest legacy to the industry. But that cuts both ways. Osborne’s son Joe, now Godolphin’s managing director, worked a season with Williams at Spendthrift; and later, when Williams teamed up with Lee Eaton to form Eaton-Williams, “Flying Start” course director Clodagh Kavanagh was among those who worked a sale or two for that pioneering agency.

In the meantime Williams had also established a small farm of his own, Ballindaggin, named for the Wexford birthplace of his Quigley grandfather. Here he raised the wonderful Flawlessly, albeit she had by no means matched her name as a weanling. Indeed, Williams told the Wolfsons that her dam, La Confidence, should maybe go to the November Sale.

“And this filly that I didn’t think much of, she won nine Grade Is,” he recalls happily. “I had a lot of conversations with Lou Wolfson. Never in any of those conversations did he close without reminding me that I wanted to sell her mother. Flawlessly was head and shoulders the best that I ever raised. An extraordinary filly. She was not sound. As a matter of fact, Chris McCarron wanted to scratch her because of how rough she was, warming up, but he was deathly afraid of the wrath of Charlie Whittingham. That was Flawlessly. She had so much heart, so much try. She was very much like her sire, Affirmed, who wouldn’t let Alydar by. See how lucky I’ve been, to be around people like Lou and Patrice Wolfson?”

Well, Mr. Williams, we all need luck; but they do say you also make your own. No doubt you miss the farm, in nowadays instead acting as consultant to a few fortunate clients; while remaining a “breeder” in owning a single mare, with longtime friend and partner Paul Manganaro; and otherwise turn those skilled hands to restoring antique boats, or building bookshelves. But your work carries on, wherever things are done properly in the Bluegrass and beyond. Your work; Billy Haun’s work; and really, as such, the work of Haun’s own teacher, Ben Jones, in Kansas in the 1930s. All true horsemanship is owed to example and now, thanks to you, a new generation can be told: “You can’t do enough for the horse. He feeds you.”

So as Williams reflects on the winner of that $5,000 claimer, over half a century ago, he can acknowledge the one, abiding credit he is glad to accept. “This reminds me not of who I was, but who I am,” he says, looking at the picture. “I am just a groom that had a good shot.”